The Landings in Normandy*

WAR in the desert had been described as “The tactician’s paradise—and the quartermaster’s hell,” a saying that must tank crews would have been quite prepared to endorse without bothering unduly how “The Q” felt about it—always excepting, of course, the vexed question of “The Bigger Gun,”

War in Normandy was about equally exasperating for everybody. Before studying the problems of armour in the planning, and the initial battles, it is worth while to summarize the enemy’s intentions, as far as they were known at the time, and also the country where we were going to fight him.

The Country

The Calvados countryside is almost equally divided between the “Bocage” and the “Campagne,” the former being, in the term, of the textbooks, “Infantry country” and the tatter “Tank country.” The “Bocage” consists of what at first sight appears to be continuous forest, but on closer inspection gives way to innumerable tiny paddocks, each one separated from its neighbour by a high bank topped with a thick hedge. These paddocks are interspersed at frequent intervals with almost impenetrable woods and coppices. The lanes, along which all progress has to be made, are narrow and banked on both sides, and not infrequently the hedgerows almost meet ever the middle of the road. In this country a field of fire of fifty yards is considered good. The whole effect of the tiny chequered fields must be similar to the one that confronted Alice when she stepped through the looking-glass—much too picturesque for war.

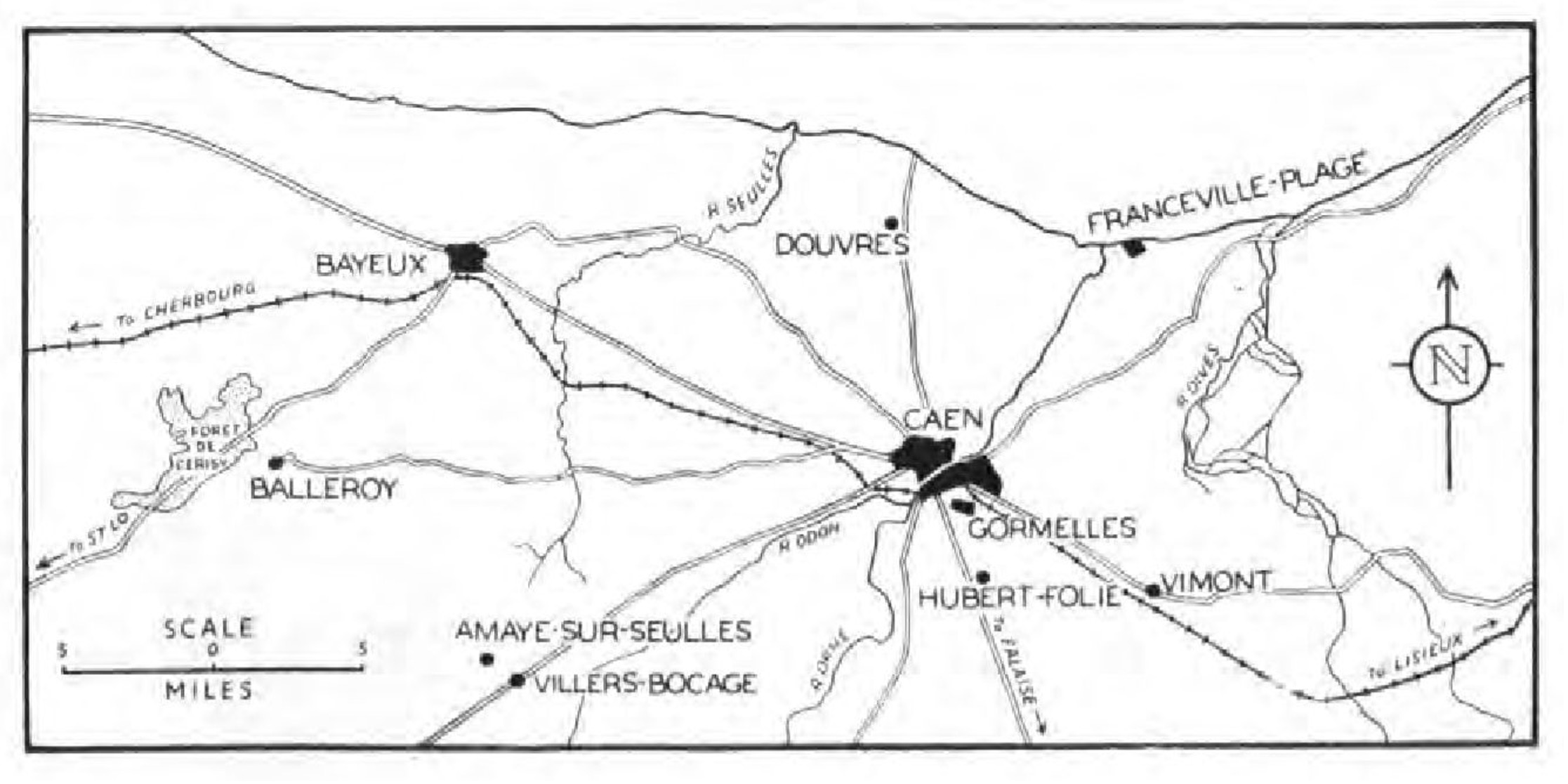

This country extended to the west and south-west of Bayeux, and everyone who came into contact with it heartily detested it, for it bore a very close resemblance to continual street fighting.

At the other end of Second Army front was the rolling plain south and southeast of Caen. Here everything was the complete opposite. There were few trees, which were mainly confined to the roads, and the huge open fields were almost without exception under crops. These fields were seldom separated by hedges or ditches, and movement across country was as easy as across Salisbury plain.

Small, grey stone villages were clustered round their churches, and the entire plain was intersected by occasional narrow river valleys with thick woods on their steep slopes.

This, then, was to be the battlefield.

German Intentions

The German tactics were to defend the coastline with second-rate divisions not equipped with adequate transport to fight a war of movement, to back these up with field infantry divisions for immediate counter-attack, and to hold back the Panzer divisions in the rear for the blow that was to drive the invaders into the sea.

This plan the Germans referred to as “Crust-Cushion-Hammer.”

On D Day the coastal crust on Second Army front was held by one second-rate infantry division with two of its regiments in the line. These regiments occupied concrete positions along the coast at intervals of approximately one mile, covering the continuous lines of mines and “Element C.” Behind them to the south of Bayeux was stationed 352nd Infantry Division, while within easy reach were the two Panzer formations, 12 S.S. and 21 Panzer, at Falaise and Bernay respectively. Also to be expected on the scene by the evening of D-1 were two further Panzer divisions, 17 S.S. south of the Loire, and 2 Panzer at Amiens. These divisions were equipped largely with Panther and Tiger tanks, both of which heavily outweighed our own tanks in armour and gunpower. Their shortcomings in speed and reliability were not to become apparent until we had achieved the break-through.

The British Plan

The main assaulting forces were to make three landings. On the left-hand sector I Corps was to make two landings, using three British and three Canadian divisions, supported in each case by an armoured brigade, while on the righthand sector XXX Corps was to assault with 50th Division, also supported by an armoured brigade. This assault was to be followed up immediately by 7th Armoured Division, who were to pass through as soon as possible, directed on Villers Bocage.

The original feature of the plan was the enormous weight of armour in the assault.

The British Armour

The inclusion of nearly a thousand tanks in the immediate assault (ignoring for the moment the invaluable “Funnies” of Genera! Hobart’s 79th Armoured Division) was something new in the technique of amphibious landings, and it is worth while to pause for a moment to examine the equipment of these formations.

The new British cruiser tank, the Cromwell, was going into action for the first time and great things were hoped from it. The Cromwell was really fast and she presented a low silhouette, while she was certainly a reliable vehicle. Her armament, however, had recently been changed from the 6-pdr to the 75-mm gun, and her armour was not in the same class as the German Panthers and Tigers that she was to meet. Only one of the four brigades was equipped with Cromwells.

The other three brigades Were all equipped with the battle-tested Sherman. The Sherman was a good tank and it had proved more than a match for the Pz. Kw. 4 in the battles in the Middle East. But once again the armour was insufficiently thick to give very much protection from the high-velocity 75-mm of the Panther or the 88-mm of the Tiger.

These tanks, however, soon found themselves in combat with both Tigers and Panthers, under conditions where they could neither make use of their superior mobility nor gain very much benefit from the alleged unreliability of their opponents.

The Assault

The assaults on the eastern beaches, and the airborne landings, had gone well and the troops were pushing inland, making satisfactory progress. As they neared Caen, however, resistance stiffened, with 21 Panzer Division in action north of Caen on D Day itself. The following day 12 S.S. Panzer Division was identified in action to the west of the town.

Clearly the enemy intended to prevent us from capturing the town, which was according to our appreciation that he would try to deny us all the ports. Caen, of course, was the sixth port of France.

Three British divisions pressed their attacks towards Caen, but without success. They found themselves confronted by the same open country as the Canadians on their right, but with the tiresome additions of prepared anti-tank ditches and concrete emplacements. Later, dug-in tanks appeared overnight which proved virtually unapproachable from the ground and seemingly invisible from the air. At all events, the initial thrust for the port of Caen was held.

The Thrust to Villers Bocage

On the morning of 12th June, the situation on XXX Corps front seemed to be crystallizing, with the enemy firm and in force in all the villages along the front, with co-ordinated anti-tank defence between them.

Accordingly it was decided to regroup and launch 7th Armoured Division on a new thrust line to swing down on the flank of 50th Division and come in on Villers Bocage from the west.

The ground was difficult for armour, but the attack, if successful, would threaten the whole position of the enemy forces covering Caen to the north. To assist this thrust pressure was to be exerted in the Caen sector by 51st Division, which had just arrived.

At first light on 13th June the advance was resumed, and although the armoured cars and the Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment were in contact with enemy on both sides of the centre line, Villers Bocage was entered without incident.

There followed a mishap that put the case against British tank design far better than a dozen speeches in Parliament could do.

A squadron of one of the armoured regiments equipped with the new British Cromwells was ordered to occupy the high ground to the north of the town, and it was followed by the RHQ of the same unit, in all, about twenty-five cruiser tanks and half a dozen light tanks of the reconnaissance troop.

The cruiser squadron pushed on and reached the high ground as ordered, and were followed by the RHQ, consisting of four Cromwells, two artillery OP tanks of the same class, some half-tracks of the motor battalion, and some light tanks of the reconnaissance troop. This force was ambushed in the narrow lanes by a Tiger tank which “stopped the earth” at either end by destroying a half-track and a light tank. It then proceeded along the column, destroying the remainder of the vehicles at its leisure, for the guns of the Cromwells were useless against the heavy armour of the Tiger, and the high banks of the road effectively prevented all power of manoeuvre. Meanwhile the Squadron had gone on ahead and reached its objective, but had been completely surrounded by infantry and Tiger tanks. The last wireless message received from them reported the position untenable, and withdrawal, because of the blocked road, impossible. Nothing more was heard of this squadron.

German "Royal Tiger"

|

Weight — 66.9 tons |

Armament |

Dimensions |

|

Armour |

88 mm and 7.92 MG |

Length — 23 ft. 10 in. |

|

Turret front — 7 in. |

Coaxially mounted |

Width — 11 ft. 11½ in. |

|

Hull front — 5.9 in. |

7.92 MG in hull |

Height —13 ft. 6½ in. |

|

Speed — 18 m.p.h. |

Radius — 105 miles |

Clearance — 1 ft. 5 in. |

What had happened to cause this sudden spate of German armour was plain enough. The anticipated counterattack by 2 Panzer, hitherto delayed by our air forces, was at last materializing and both sides had arrived at Villers Bocage simultaneously.

Fortunately the surprise was mutual.

This piece of deduction was confirmed by the action of a sergeant of the Armoured Car Regiment who was taken prisoner, but on realizing the identity of his captors, and appreciating the importance of the information, succeeded in killing one of his guards and taking the other one back to his unit for interrogation.

A force for the defence of the town was hastily organized, but the German tank attack having been beaten off, a more serious threat developed, that of infantry infiltration supported by heavy artillery fire. The garrison of the town was hopelessly inadequate, being about one infantry battalion and one squadron of tanks in strength, and to have reinforced it would have risked the entire force being cut off. It was therefore decided to withdraw about seven miles to the area of Amaye-sur-Seulles, where it was hoped that 50th Division would be able to make contact. The withdrawal was carried out without undue incident, and a tight “box” was formed some two thousand yards by fifteen hundred. It was the nearest thing to a British square seen in this war and the enemy behaved as all enemies have always done when confronted with this situation. He flung everything he had at the “island” as it was called, and attack after attack was repulsed with heavy losses. The Artillery on one occasion broke up one attack with Bren guns and airburst at four hundred yards’ range.

The position again became untenable, with no immediate prospect of an advance by 50th Division, and it was again thought necessary to withdraw.

This twentieth-century “Quatre-Bras” came to an end on the night of 14th June when the weary columns pulled out of “the island” position. The noise of the tanks’ engines was drowned by a heavy bomber attack on what was fondly imagined by all concerned to be Villers Bocage. The RAF, however, had got their maps upside down or something, and punished instead the little village of Aunay-sur-Odon, some four miles to the south.

The extent of the defensive victory gained at Villers Bocage did not become apparent till later. It was known that exceedingly heavy casualties were inflicted on the enemy in both men and vehicles—on the final day in the “island” forty tanks were claimed destroyed—but it was not realized at first that the German High Command had been trying to drive a wedge with 2 Panzer Division between the American and British Armies through Balleroy and the Foret de Cerisy. As it turned out, 2 Panzer Division had been severely crippled as an offensive fighting force at a crucial stage in the battle, and the fighting had given our infantry a feeling of moral superiority that stood them in good stead in the weeks to follow.

The Increase in Panzer Opposition

In the meantime, the attack by 51st Division against Caen had not been making very much progress. The arrival of VIII Corps had been delayed by the weather, and the enemy had deployed four Panzer divisions opposite the British front by the end of the 18th June.

The VIII Corps attack started well enough, bridgeheads being established over the Odon River and 11th Armoured Division reaching the high ground that dominated the crossing at Point 112. VIII Corps was particularly strong in armour for this attack, having under command 11th and Guards Armoured Divisions, and two additional armoured brigades. However, on 29th June, this advantage was offset to a certain extent by the identification of two new Panzer arrivals, 1 S.S. Panzer and 2 S.S. Panzer Divisions, Moreover, the vultures were gathering, for on the following day, 30th June, a further two arrivals were reported in action, the 9 S.S. Panzer and 10 S.S. Panzer Divisions. This made a total of eight Panzer divisions on the twenty miles of front of Second Army and, so as not to provide the vultures with a feast, it was decided to concentrate on holding the gains already won by the XIII Corps offensive without pressing for the Orne bridgeheads, and to withdraw the armour into reserve ready for another thrust.

The “Drawing Powers” of Second Army Attacks

As the time for the break-out drew nearer and the enemy showed signs of anxiety about the western end of the Allied front, Second Army were told to go ahead with the capture of Caen, in order to dispel any notions that the enemy might have about transferring some of his Panzer forces farther west. Care had to be taken not to be caught off guard by a large-scale counter-attack.

The attack on Caen went in on 7th July, and the operation lasted two days. The preparation included a very heavy “saturation” attack by Bomber Command, consisting of 460 heavies, each carrying five tons of bombs. The bomb line was 6,000 yards in front of the forward positions on the ground, and the interval was given a “working over” by massed artillery. The attacking forces were to consist of three infantry divisions supported by two armoured brigades.

At 2200 hrs on 7th July, the bomber attack went in, and at 0420 hrs the following morning the attacking troops crossed the start line.

The attack fell on the newly arrived 16 G.A.F. Division, and by 9th July, the whole of Caen was in our hands.

“The Curtain Raiser”

The American attack had originally been visualized as being launched in the middle of July, The Americans, no less than anyone else, had been delayed in their build up by the weather and the target date for the assault had to be postponed for about ten days. The postponement correspondingly increased the difficulty experienced by Second Army in maintaining their threat to break out of the Caen hinge.

The Germans were already showing decided signs of anxiety about the ominous calm on the American sector, and it was agreed that the preliminary feint to the American attack by the Second Army must be on a grand scale to continue to hold the enemy’s attentions.

A plan was made to launch three armoured divisions, supported by a colossal air programme, in a drive to the south-east of Caen, directed on Falaise. Meanwhile XXX Corps were to develop operations towards Thury Harcourt on the central sector of the British front.

The orders were to “cross the Orne to the north of Caen, and to turn southeast, where the armoured divisions were to be established in the areas Vimont, Hubert-Folie, Verrieres.” They were “to dominate the area and fight the enemy armour which would come to oppose them. Armoured cars were to be pushed out towards Falaise in order to cause the maximum dislocation to the enemy.”

It was an interesting conception. It had been proved time and again that armoured battles were not a paying proposition, and what sort of dislocation the armoured cars were expected to cause with their 2-pdr guns in an area known to contain a Panzer division equipped with Panther tanks was never satisfactorily explained.

It is now common knowledge that the attack gained about ten thousand yards and then stuck. At the end of the first day of fighting the tank casualties of the armoured divisions were well over 150 tanks destroyed, but it was established that, in spite of having brought 16 G.A.F. Division, 276th Infantry and 277th Infantry Divisions into the line, the only Panzer division not committed by 18th July was 12 S.S. Panzer.

Certainly the German armour was drawn sharply hack into the battle. Having accomplished this, our own armour was withdrawn into reserve ready for the next thrust, and the infantry took over the sector on 20th July.

Five days later the Americans launched their break-out.

It is interesting to glance briefly at the following table of the dispositions of the Panzer divisions at various stages, during the bridgehead fighting:—

|

|

Gaumont-Caen Sector |

Remainder of front |

|

Mid-June |

4 |

0 |

|

Early July |

7 |

½ |

|

Mid-July |

6 |

2 |

|

July 20th |

5 |

3 |

There is no doubt that these divisions were worn out by continual recommitment, first in one sector and then in another, and towards the end of July they were severely under strength in both men and tanks. The all-out attack at Mortain was the last major effort of which they were capable, but it was too late.

Epilogue

Perhaps the best comment on the whole battle of Normandy was made by the Colonel commanding a battalion of Canadian Infantry. Two tank columns of different armoured divisions, both in search of the enemy, met head-on on a fourth-rate track outside his headquarters near Cormelles.

“What beats me” he remarked to the leading troop officers, “is why we didn’t bring over one Piccadilly Bobby as our secret weapon. He would have won us this war in half the time.”

“A good commander is a man of high character. He must know his tools of trade; he must be impartial and calm under stress; he must reward promptly and punish justly; he must be accessible, human, humble, and patient. He should listen to advice, make his own decision, and carry it out with energy.”

— General Joseph W. Stilwell, U.S. Army.

* From the Royal Armoured Corps Journal, January 1948.