There is no more challenging role in the Australian Defence Force (ADF) than to command in war.

ADF-P-0 Command[1]

Command is not easy. In peace or war, command is one of the most difficult activities we do as military professionals. Command in the Australian Defence Force (ADF) is unique—very few organisations can knowingly order subordinates into life-threatening situations. It takes a great deal of training, education and experience to be ready to command, and then the execution of command takes constant work at the personal level. Given the enduring human nature of war,[2] even in the face of increasing technological advances, enabling successful command should be an absolute priority. If we want to be able to use the benefits that command gives us, we need to be doing everything we can to enable it in wartime while we are at peace.

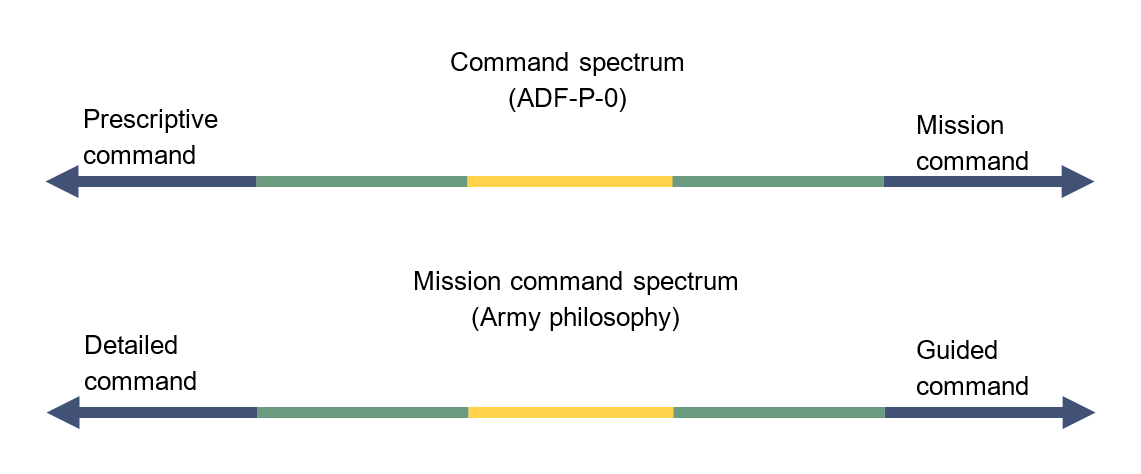

Doctrinally, ADF-P-0 Command provides a concept of command as a spectrum with prescriptive command (requiring the commander’s personal direction and detailed instructions) at one end and mission command (relying on subordinates’ knowledge of the mission and purpose to guide decisions) at the other. This concept of command is a shift in language and terminology by the doctrine’s own admission. This doctrine marks a change for the ADF in ‘moving away from [a] unitary concept of mission command towards the concept of command on a spectrum’.[3]

For Army, the concept of command is mission command and it is not unitary in nature. There is a spectrum within mission command ranging from detailed command to guided command. A comparison of the two concepts is summarised in Figure 1. While on the surface it may seem that the change has been a superficial one of ‘re-badging’, the concern of this author is that the shifting of this terminology has confused the idea of a single concept of command.

This article will explore Army’s use of mission command across the spectrum.

Mission command can be poorly understood even by its practitioners. Its exercise is not simply about standing up and telling people what your intent is and sending them off to do their best in accordance with your instructions. At its heart, mission command is an extension of philosopher Immanuel Kant’s assumption that every worthwhile man will always do his duty to the best of his ability. The extension is that every soldier, from private to field marshal, must be brilliant at the fundamental warfighting skills associated with their station; further, they will always execute those skills to the limits of their exertion.[4]

Army’s association with mission command over the past 50 years has led to significant in-service discussions over its utility, efficacy, benefits and drawbacks. Perhaps the fundamental lesson out of these discussions has been to acknowledge that all spectrums of mission command are applicable to some situations, and one cannot associate battlefield success only with the idealised version of the concept, namely ‘guided command’. Indeed, the use of ‘detailed command’ can be ideal in certain situations to get tasks back on track or to attempt to manage an impetuous subordinate. For example, following a mismanaged assault on an enemy strongpoint by a subordinate, a commander would be justified in giving detailed guidance to the subordinate in a subsequent action or operation, both to secure success and to mentor that subordinate and show them a ‘better’ way.

In 2011 then Lieutenant Colonel Rupert Hoskin provided a further critique of how commanders can mismanage guided command, stating:

All too often, people claim to be mission commanders in the belief that staying out of the subordinates’ way is a virtue in its own right. This is simplistic and lazy. What tends to happen is that the subordinate gets poor initial guidance (‘I’m busy and it will do him good to work it out for himself, and I can assess him better this way’), then cracks on manfully until things stray from the commander’s (belatedly considered) intent. By then it’s too late for a light touch and the commander re-injects himself to get things back on track, employing tight control and leaving all parties disgruntled. It is all very well to let people learn from their mistakes, but in reality it is wasteful to make a habit of this: while one leader executes his flawed plan, his subordinates are learning bad lessons, getting frustrated and expending scarce resources. Better to let the lesson be learned ‘virtually’, via the back brief process, then reinforce success via execution of a good plan.[5]

Mission command is erroneously employed by many commanders with a hands-off approach, exactly as described by Hoskin above. This would be workable had the commander given appropriate guidance, resources and supervision. The level of appropriate guidance and supervision is determined by the level of mutual understanding,[6] and trust, the commander has with and in the subordinate. That trust is established through education, training and shared experiences.

Building Trust—a Head Start

How do we institutionally build this trust and how can we as commanders ensure we build on it constantly? The Australian Army is a very different organisation to civilian or other government agencies across Australia. Unlike a headhunted CEO parachuted in to run a civilian organisation, every Chief of Army (or Chief of the General Staff (CGS), as the position was called before 1997) since Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Daly has been largely educated and trained within the Australian Army and the ADF.[7] Each Chief of Army knows his subordinate commanders—and has for over 25 years in many instances. He may have gone through Royal Military College, Duntroon with them as a peer or superior, and instructed or led subordinates on courses or in units. Since the appointment of Lieutenant General Ernest Squires as CGS in 1939, the Australian Army has not appointed a soldier of a different army as its professional head, and it is very unlikely this would occur again, owing to the degree to which it would undermine Australian sovereignty and social legitimacy.[8] This almost intimate knowledge of peers, near subordinates and superiors allows for an environment of shared education, training and experiences that is not present in other organisations. This is an excellent institutional start.

Trust enables freedom of action—the higher the level of trust, the more likely that a commander will enable a subordinate to execute more freely. There is a bill to be paid before mission command can ultimately be used successfully across the left and right extremes of the spectrum. That bill—generating that trust—is paid in education, in training, in shared experiences and in execution.

Educating about Mission Command

Mission command is not some kind of laissez faire anarchy …

ADF-P-3 Campaign and Operations Edition 3[9]

Educating people about mission command is akin to forcing people to read Carl von Clausewitz’s or Antoine-Henri Jomini’s vast tracts on war, not just google them for quotes. The common misconception is that mission command is all about full freedom of action by subordinates. Commanders and subordinates alike fail to understand the spectrum and what must be done to enable its use between the extremes. At the first use of detailed command, subordinates can complain of micromanagement, often not appreciating why it is being used. The principal use of detailed command, as noted above, is by commanders who seek assurance that key tasks get done through the means they desire, and this may include technical or procedural tasks. Fundamentally, the commander has the intrinsic right to give detailed guidance on any task. If operational success is the responsibility of the commander, and if this hinges on a crucial event, it is natural for the commander to become detail oriented and get intimately involved in such an operation. This is why we must educate on the spectrum of techniques available for mission command.

Another common use of detailed command is when a commander is assigned subordinates who they may not know or trust. In this situation, the commander can use their presence and experience to ensure the potential success of an operation. Alternatively, an event may be so detailed—breaching a minefield or marching a large organisation on multiple routes, for example—that precisely following orders is required. This is still within the spectrum of mission command. Detailed command is micromanagement—there can be no doubt on this—but there are many circumstances in which a commander, with more years of experience than their subordinate, recognises that they need to impose themselves on a situation to ensure success. Commanders are right to use it—to impose their skills on a tactical situation, using years of knowledge and skill to reinforce a young officer with less experience, to ensure success.

There are numerous examples of detailed command being used within a mission command system by both Allied and Axis forces in World War II. For example, in July 1944 Major Hans von Luck, a German Army battle group commander, directed, at gunpoint, a Luftwaffe air defence battery commander located in Cagny, France, to redeploy, where to deploy to, what direction to face and what to shoot at[10]—directing the battery commander to stop firing at Allied bombers and instead to focus upon British tanks. This direction provided invaluable support to the disruption of Operation Goodwood in his area. While the extent to which the United States Army of the Second World War utilised a mission command style system can be debated, the exercise of detailed command nonetheless also occurred. In France in August 1944, Lieutenant General George Patton found his 3rd Army trapped in a traffic jam in Avranches. Patton intervened, and for 90 minutes he personally directed traffic. In this instance, the insertion of his command presence and experience sorted out the jam, whereas a lesser subordinate might have had extreme difficulty.[11] This is an example of detailed command—precisely telling individual anti-air gunners where to position themselves, and drivers when and where to go. Such circumstances may seem its antithesis, but they are still within the spectrum of mission command.

Detailed command, however, can become dangerous to an organisation when a commander uses it all the time. Subordinates can begin to feel stifled or resentful of such ‘interference’ or lack of trust. Understandably, then, subordinates are generally dismayed at this end of the arc of mission command. It is common for each subordinate to believe that guided command is the right, and the only, use of mission command.

The principles underlying guided command[12] are perhaps the most commonly known throughout Army. It ostensibly allows a subordinate maximum flexibility to choose the way a task is to be achieved, fostering a greater tempo by decentralising decision-making, allowing the commander on the ground to assess the situation and make an appropriate decision. This ideal should be sought when appropriate. Nevertheless, and as previously noted, its successful achievement requires trust between a commander and their subordinates and an understanding of their capabilities. For subordinates, the real value of understanding a commander comes when the situation that presents or develops is significantly different from the estimate used during planning. When this occurs, commanders rely on their subordinates to execute a number of critical abstractions as follows:

- Correctly identify that the situation they see is indeed nothing like that planned for and, as a result, large parts of their plan (if not the whole thing) are rendered irrelevant.

- Develop their understanding of what the situation actually is.

- Estimate their commander’s intent given that the situation has changed. In this instance answering one simple question should do the trick: ‘If my commander were here and understood the actual situation as I do, what would he want me to do?’

- Generate and implement a solution, within their (the subordinate commander’s) authority, to achieve the previously articulated end state. Alternatively, if that end state is no longer valid, then the new plan should reach an end state that is at least beneficial to friendly forces, ideally while deteriorating the capacity of the enemy.

Guided command allows for decentralised decision-making at the lowest levels. Time previously spent reporting, creating a picture at higher headquarters, solving the problem, giving orders back down the chain of command and then executing the mission is no longer required. This is because the commander at the point of contact has been empowered to decide and act. This situation potentially generates a significant advantage for the ADF in operational tempo, especially if we face an opponent that favours a centralised model.

How We Get There—Educating and Training

Education and training are a responsibility for every commander at all levels—they are what we do every day in barracks and in the field. Good units continue to educate and train even when deployed. For example, in 2001 in Suai, East Timor, Headquarters Sector West conducted a weekly command post exercise (CPX) to drill lessons learned from that week’s operations. This practice was only cancelled in the event of an incident.[13] Our core role as commanders is to ensure that we educate and train subordinates to solve problems, convey intent, lead and then learn from the experience—four critical skills that must be developed and practised. Training must be relentless—everything that we can turn into a drill should be repeated until no thought is required. Repetition in training allows us to save the brain from fatigue. The most precious thing we have is the ability to solve new problems—we should not be wasting it solving the routine and mundane activities.

This education and training should include tactics—the constant building of a mental library of tactical events that builds the ‘pattern recognition’ essential for tactical success. Tactical decision-making often relies on pattern matching and heuristics, the development of which requires significant training, education and experience to build up a ‘library’ to be called upon by the commander. There are very few scenarios that have not occurred in some form or another in history. Competent tacticians identify a tactical scenario, compare it to one they have either learned about or previously practised, and then apply a solution that worked, with tweaks to account for contextual differences. The larger the mental library a tactician has, the better they will perform.[14] Tactical exercises should never have a school solution.[15] There are no right answers in tactics.[16] There are solutions that might work and solutions that might not work, but we can never assume that our seemingly perfect solution will be unaffected by chaos, friction, uncertainty and chance. Equally, we should not overlook the fact that a solution that looks unlikely may be hit by a ‘lucky bolt’ from the sky.[17]

There are two important components of this tactical education and training. The first is to ensure that a timely decision is made. Subordinates should be encouraged when they make a decision, even if it is wrong.[18] A quick wrong decision can be corrected by a quick correct second decision—the important bit is to encourage subordinates to make decisions. As noted in Truppenführung (‘Handling of Combined-Arms Formations’):

The first criterion in war remains decisive action. Everyone, from the highest commander to the youngest soldier, must constantly be aware that inaction and neglect incriminate him more severely than any error in the choice of means.[19]

The second component of education and training is for commanders and subordinates to share perspectives on how and why a solution was attained. This allows them to understand how, respectively, they think tactically and solve problems. This is a critical experience—if we know how we approach tactical problems, we have a much better understanding of the capability of each other.[20]

In shaping tactical problems for consideration, trainers and educators should include scenarios that are not tactically feasible. For example, there is value in forcing ratios way out of acceptable ranges, as this will generate innovative and instructional discussion and thinking. Problems should always be incomplete, fragments of what is expected in reality. This promotes comfort with uncertainty—100 per cent situational awareness is unlikely to be achieved, and we should be prepared to conduct activities knowing the bare minimum.

Shared Experiences

Generating shared experiences is likewise a core activity. Such experiences do not have to occur exclusively in the context of field exercises. Shared experience will also be stronger when there is a perceived (or actual) threat of harm to the individual, but it is not limited to these situations.[21] Physical training, adventure training, team sport and even social events all generate shared experiences. These shared experiences—bonding over events and testing activities—further build the level of trust between subordinates and commanders.

The only way to generate understanding of subordinates, including of their strengths and weaknesses, is through personal familiarity with them, or observation of their training, education and abilities. The commander’s responsibility to educate, train and test subordinates, therefore, is a means of generating trust and understanding. This, however, goes both ways. Through their own observations, a subordinate will develop a better understanding of their commander’s abilities and, hopefully, develop trust and faith in the commander’s higher direction.[22] Only through this mutual knowledge can a commander know when to impose in the process—and when to remove themselves and trust the subordinate to do the job they have to do.

Mission Command in Execution

The commander plays the lead role in executing mission command. It is, and should be, mentally and physically exhausting. Knowing where to be physically located and when to be there, checking subordinates’ welfare, giving guidance to staff—the bill on the commander is great and consuming. A commander’s staff are critical in this aspect. Competent staff, led by a chief of staff, must remove all but the most critical of decisions to be made by the commander, not bogging the commander down in the mundane. This is a critical function—executing mission command requires the active participation of the commander and they must be kept as free from minor decisions and situations as possible.

The execution of mission command requires a great deal of detailed planning and coordination by a commander’s staff. Enabling mission command in execution requires thorough and detailed staff work to ensure that forces are in the right place at the right time, armed, fuelled and prepared. The ‘right of arc’ of mission command cannot be used for staff work. Planning goes beyond the commander’s ‘intent’ paragraphs in operational orders. Staff work needs to be thorough and fully integrated across the arms corps and all affected services. Currently, our planning and orders doctrines enable mission command. In a set of SMEAC (situation, mission, execution, administration/logistics, command/signal) orders, subordinates get a series of tasks, not a mission. This situation allows them to compose their mission and the way the tasks are to be executed. Any tendency to airily dismiss the relevance of logistics, traffic control or personnel management will see every good plan come crashing down—the execution bill must also be paid in staff work.

Execution of a commander’s intent must be supported by thorough staff work. This takes time, expertise and a competent headquarters with trained staff. Post ‘H-Hour’ needs staff support just as much. Staff must keep abreast of the changing situation and changing commander’s intent, recognise for themselves when the situation has changed, and enable subordinates or point them in the new direction.

Conclusion

Army inherently uses mission command as its command philosophy. Mission command has a spectrum of command from detailed command to guided command, and the flexibility to adapt the philosophy depending upon the situation. Both extremes of the spectrum are perfectly acceptable to use at the right time and place. The challenge for commanders is, of course, knowing when and where to use this spectrum—knowing when to impose themselves and when to let subordinates act independently within the intent.

This is where paying the mission command bill comes in. We pay this bill in training, education and building shared experiences with subordinates and superiors. This generates trust and understanding of our actions. It also creates thought patterns under stress, when tired, when hungry and when the real fear of life is upon us. Warfare is a fundamentally human affair. It is about imposing our will on the enemy and upon our subordinates to do our bidding—bidding that often involves unpleasant and unnatural things.

Command is not easy. Mission command gives us the flexibility to ensure that the correct command technique is available when required. Mission command works best when we pay the bill first—a bill not paid by arriving and expecting complete trust and understanding. Spend the time, build the trust, educate, train, ensure the mutual understanding, and know subordinates and superiors. By educating, training, sharing experiences and executing Mission Command appropriately, the Australian Army can move beyond the point we are currently at and start taking advantage of the tremendous advantages that mission command can give us.

Endnotes

[1] Australian Defence Force, Command, ADF-P-0, Edition 1 AL 1 (Canberra: ADF, 2024), p. 1.

[2] Lieutenant General Simon Stuart, ‘The Human Face of Battle and the State of the Army Profession’, speech, Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre, 12 September 2024, at: www.army.gov.au/news-and-events/speeches-and-transcripts/2024-09-12/chief-army-symposium-keynote-speech-human-face-battle-and-state-army-profession.

[3] ADF-P-0 Command, p. 6, point 6 ‘Scope’.

[4] See Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, trans. and ed. Mary Gregor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). Thanks to BRIG Grant Chambers for this insight.

[5] Rupert Hoskin, ‘Reflections on Command’, Australian Army Journal 8, no. 2 (2011): 175.

[6] On the German Art of War: Truppenführung, trans. and ed. Bruce Condell and David T Zabecki (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001), p. 18.

[7] It was not until the Second World War that Army began to provide most forms of the formal professional education system. While Duntroon was established in 1911, Army lacked post-commissioning professional military education facilities such as a Staff College or War College, with only a select few officers sent to such British establishments. Sir John Lavarack, CGS from 1935 to 1939, was the first CGS to spend the entirety of his career within the Australian Army (his predecessors had been commissioned into the state-based colonial armies), and he attended Staff College and higher studies in Britain, as did many of his successors. General John Wilton was the last CGS who served in another military, as he was commissioned into the British Indian Army and spent his formative years in that service. Many members of Army of course continue to attend overseas education, such as the US Army Staff College, but this is to support interoperability rather than as a replacement for a sovereign Army education system. See Jordan Beavis, ‘A Networked Army: The Australian Military Forces and the other Armies of the Interwar British Commonwealth (1919–1939)’, PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, 2021; Brett Lodge, Lavarack: Rival General (Allen & Unwin, 1998); Sydney Rowell, Full Circle (Melbourne University Press, 1974); and David Horner, Strategic Command: General Sir John Wilton and Australia’s Asian Wars (Oxford University Press, 2005).

[8] Beavis, ‘A Networked Army’, 195–197.

[9] Australian Defence Force, Campaign and Operations, ADF-P-3, Edition 3 (Canberra: ADF, 2024), p. 51.

[10] Hans von Luck, Panzer Commander: The Memoirs of Colonel Hans von Luck (New York: Dell, 1991), pp. 193–194.

[11] Carlo D’Este, Patton: A Genius for War (New York: Harperperennial, 1996), p. 628.

[12] With the reviewer, there was a lot of discussion about what to call this end of the arc. ‘Full freedom’ was first used but caused too many issues.

[13] The author served as Captain S33 in HQ SECWEST in 2001.

[14] General Mattis states that the problem with being ‘too busy to read’ is that you learn by experience, i.e. the hard way. Instead, he suggests that by reading, you learn through others’ experiences, which is generally a better way to do business. He says, ‘Thanks to my reading, I have never been caught flat-footed by any situation, never at a loss for how any problem has been addressed (successfully or unsuccessfully) before. It doesn’t give me all the answers, but it lights what is often a dark path ahead.’ He reminds us that human beings have been fighting on this planet for 5,000 years, and that it would be foolish not to take advantage of those who have gone before us. See Jim Mattis, Call Sign Chaos (New York: Random House, 2021), pp. 256–257.

[15] Stephen Lauer, Forging the Anvil: Combat Units in the US, British, and German Infantries of World War II (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2022), p. 99; Jorg Muth, Command Culture: Officer Education in the U.S. Army and the German Armed Forces, 1901–1940, and the Consequences for World War II (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2011), p. 165.

[16] James Corum, The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992), p. 92.

[17] My thanks to LTC Steve Duke, a US Army exchange instructor at Combat Command Wing, School of Armour in 2003, who drilled this into his studies (and this author) on a Combat Officers Advanced Course.

[18] On the German Art of War, p. 19.

[19] Ibid., p. 19.

[20] COMD 7 BDE DIRECTIVE 01/25—7 BDE PROFESSIONAL MILITARY EDUCATION (PME) 2025 at BQ74802188

[21] Jeremy Barraclough, ‘The Resilience Adventure’, Grounded Curiosity, 22 September 2016, at: https://groundedcuriosity.com/the-resilience-adventure/.

[22] On the German Art of War, pp. 18–19.