Debating the Australian Army Profession

In the long history of the Australian Army, there has been no significant, holistic study of the Australian Army profession, past, present or future.[1] This is an awkward statement in an introductory article to a special themed edition of the Australian Army Journal (AAJ), a publication which for 10 years (2003–2013) bore on its title page the phrase ‘For the Profession of Arms’.[2] It is rendered all the more uncomfortable by recalling that the army profession has existed in Australia, in various states of maturity, for 160 years; it was in the 1860s that the colonial governments of Australia began to appoint permanent staff to instruct and administer their volunteer militias.[3] Sliding this date to 1 March 1901, the birthdate of the Australian Army through the combination of these colonial military forces, scarcely softens the point. It has been 68 years since US political scientist Samuel Huntington published The Soldier and the State, which provided the first modern framework for analysing military professionalism; 65 years since Morris Janowitz continued and deepened this analysis in The Professional Soldier; and 63 years since Lieutenant-General Sir John Hackett delivered his famous, longitudinal lectures on the ‘profession of arms’ at Trinity College, Cambridge. Many more such dates could be identified, such as the establishment of the Royal Military College, Duntroon (1911) or the creation of the Australian Regular Army (1947). It seems, then, an oversight, if not an outright failure, that no such Australian study has been undertaken on the army profession as a whole, or even a framework for such a study developed. And it is.

This is not to say that the Australian Army’s unique history, its relationship to society and government, its methods of discipline, its culture and ethos, and its significant expertise have gone unstudied. In particular, Army’s history has been well explored. Although there are always new questions to ask or facets to examine, a wide array of studies on Army’s history exist on topics as varied as military strategy, campaigns and battles, unit and corps histories, prisoners of war, gender, sexuality, equipment, innovation, Army and society, biographies, and almost everything in between.[4] This is a vibrant military history industry, nourished by the efforts of a community of dedicated historians, just as there are dedicated Australian scholars of civil-military relations, military law and military sociology.[5] What is missing, however, is the combination of these too-often siloed specialisations into a holistic examination of what constitutes the Australian Army profession, its key characteristics and features, how it differs from or relates to the other military professions and the broader ‘profession of arms’, or even a justification for its existence or status as a ‘profession’.[6] Together, such factors form a theory of the profession—a foundation for its application on behalf of society.

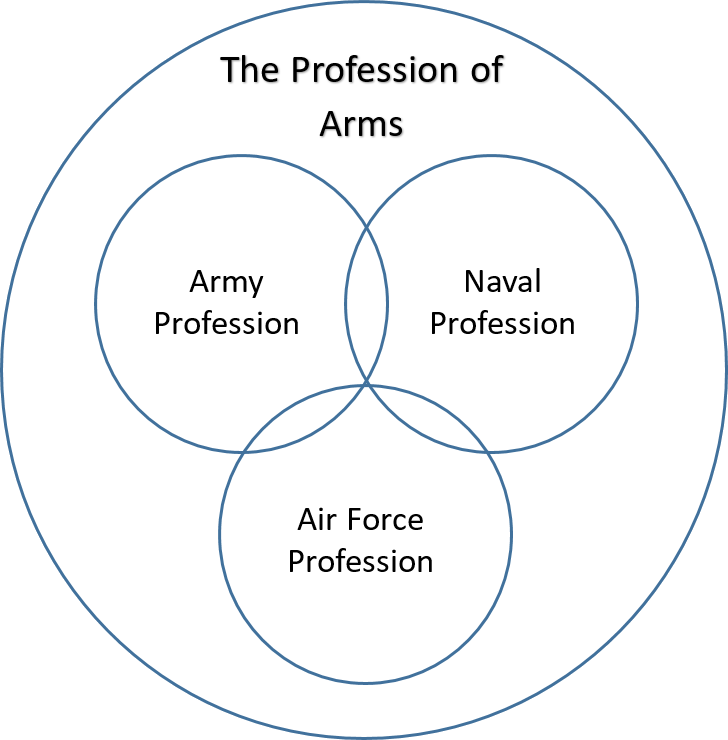

This, then, leads to a further question: why? Why has the Australian Army, despite its 124-year existence, neglected investigation into the nature of the unique profession that underlies its considerable capability? Two principal factors stand out. The first is the relationship between the ‘army profession’ and the broader ‘profession of arms’. The term ‘profession of arms’ has a long history, but it gained popularity in the 19th century as a synonym for ‘army’ or ‘military’, or to describe the action of serving such an institution as a commissioned officer.[7] In his 1810 military dictionary, British Major Charles James claimed the ‘profession of arms’ as the domain of officers, arguing additionally that there was no other profession with so ‘grave’ a responsibility—being ‘charged with defending the state’—and none that required ‘greater knowledge and capacity than the army’.[8] Across the Atlantic in the United States, the term became tied to the concept of a standing army, namely ‘a body of men exclusively set apart and employed in the profession of arms, as distinguished from militia’.[9] By the 1850s, officership in the British Army, from which the Australian Army draws its heritage and oldest traditions, was seen to be socially on par with the status of the clergy, law and medicine, despite its isolation from these other professions and ‘society as a whole’.[10] It was this continuing cultural and social perspective on the military profession in Britain, in its former dominions and in the United States that provided the foundation upon which Hackett popularised the term ‘profession of arms’ for contemporary and subsequent generations through his 1962 lectures at Trinity College, his 1983 book, and a variety of public and professional appearances and writings.[11] This popularisation had its own impact on Australia. In the 1960s, for example, the opportunity to join the ‘profession of arms’ was used as a slogan to support recruitment into the Regular Army. Later, in the 1970s, institutional reform of the ‘profession of arms’ followed many years of operations in the Vietnam War.[12] Today, the ‘profession of arms’ is no longer the domain of a single service but instead sits within the responsibility of the Chief of the Defence Force. It is used to refer collectively to ‘people practised in the ethical application and exercise of lethal force to defend the rights and interests of the nation’, namely the members of all three services.[13]

The term ‘army profession’ has, comparatively, a much shorter lineage, both internationally and in Australia. The terms ‘army’ and ‘profession’ have often been linked and have been used for a similar length of time as ‘profession of arms’—and were often synonymous with it.[14] However, the modern concept of the ‘army profession’ is much younger, being developed in the late 20th century. It has come to the fore as a result of the integration of Western armies, navies and air forces into unified organisations, à la the Australian Defence Force, the United States Armed Forces or the British Armed Forces. Centralisation of the services can be expressed through a common legislative framework that ties all services into a ‘joint’ or ‘integrated’ organisation, such as the Australian Defence Act 1903 or Title 10 of the United States Code. It can also occur through the establishment of joint bureaucracy or political oversight, such as a single ‘Department of Defence’ with a single responsible minister, rather than distinct departments of war, navy or air with their own responsible ministers. With such centralisation it is perhaps natural that the ‘profession of arms’ becomes a term used to bind all services into a joint ‘profession’ with common values or ethos (important for integrated operations). Yet fundamental differences in the expertise required, manner of regulation, and character of war across the five military domains (land, air, maritime, space and cyber) count against such a combination. Indeed, they have led some to espouse the existence of sub-professions within this broad ‘profession of arms’, such as the ‘army profession’, the ‘air force profession’ or the ‘navy/naval profession’ (see Figure 1).[15] In 2002, for example, Don M Snider and Gayle L Watkins argued that the United States had ‘three military professions: army, maritime, and aerospace’, with these being generally but not wholly contained within their own departments, surrounded by the Department of Defense, Congress and the Executive, and existing simultaneously as both professions and government bureaucracies.[16] Yet it has taken 23 years for the Australian Army to consider and adopt such terminology, and it has done so only through the advocacy of Chief of Army Lieutenant General Simon Stuart, rather than through a form of intellectual and academic introspection on what it means to be a member of the Australian Army.

What then is the second reason for the lack of a sustained, holistic study of the Australian Army profession? Ironically, the answer can be found in Army’s continued reliance (often without discernment) on international ‘profession of arms’ literature from two of its closest partners, the United States and Britain. On the whole this situation has benefited the institution: the Australian Army has found utility in the classic words of Huntington, Janowitz and Hackett, and can look further to the work of Sam C Sarkesian, Charles Moskos, James Burk, Jacques van Doorn and a host of contemporary scholars for insight into the nature and character of the military profession in the global West.[17]

Yet those seeking to apply these writers’ works to the Australian context can often look past a fundamental factor, namely that these writers and their works are the products of their specific contexts and that their arguments and insights have various degrees of applicability to the Australian Army. Indeed, the nature of professions is such that they operate differently across national boundaries. Factors such as legal and regulatory frameworks, demographics, social and cultural attitudes, and education requirements culminate to render, for example, an Australian lawyer and an American lawyer members of unique professions, despite commonalities in the task being performed.[18] Just as the nature, context and practice of professions such as law or medicine vary across borders, so too do those of the ‘profession of arms’ and the ‘army profession’. It is for this reason that even closely allied militaries pursue interoperability. Interoperability between the Australian Army, the United States Army, the United States Marines, the British Army, the New Zealand Army or any number of other regional partners is necessary owing to often significant differences in doctrine, equipment, standard operating procedures, expertise, methods of self-regulation, and culture. Just as the Australian Army cannot, without serious study and possible changes to methods, organisation, culture or equipment, adopt ‘off the shelf’ a piece of foreign doctrine, neither should it uncritically use overseas literature on the profession of arms and the army profession when discussing unique aspects of the profession in Australia. Such works can undoubtedly provide insight and inspiration, especially when they discuss the military profession from a broad Western democratic viewpoint. Nevertheless, it should not be assumed that specific case studies or mechanisms are relevant to Australia’s unique context. The risk of such a reliance is compounded by the unfortunate fact that Australia lacks a tradition in Australian Defence Force (ADF) or academic research around the profession of arms or the army profession; it is a sovereign capability every bit as important to Australian military power as a strong defence industry.

The Contemporary Australian Army Profession

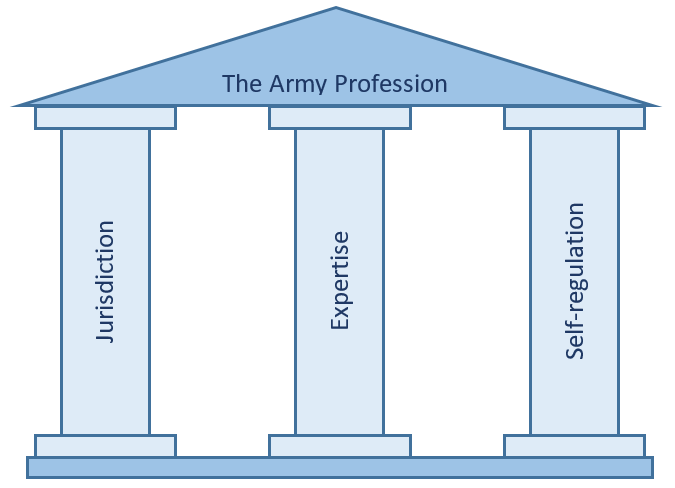

With these considerations in mind, over the last two years, on multiple occasions in 2024 and 2025, Chief of Army Lieutenant General Simon Stuart has provided clear guidance on what he, as the lead steward of the Army profession, views as the key characteristics of the Army profession in Australia.[19] Drawing critically upon the work of Huntington, Janowitz, Hackett and Burk, Stuart has identified ‘three pillars of the modern Army profession’, namely jurisdiction, expertise and self-regulation (see Figure 2). Together, these three pillars form the foundation of Army’s considerable capability as the ‘integrated force’s experts in land combat’.[20] The pillars are mutually supporting—the weakening of a single one undermines the viability of the profession and causes it to collapse beneath its own weight. Each requires a brief introduction here.

Jurisdiction, as the first pillar of the Army profession, has been defined by Stuart as the ‘unique service we provide to society as its army’. As he rightly noted in November 2025, Army ‘exists only to serve society, and we can only provide our unique service when our society requires and directs us to do so’.[21] The name of this pillar is drawn from the work of James Burk, who—drawing upon the theories of noted sociologist Andrew Abbott—argued in 2002 that a profession required a ‘field of endeavour … for problem solving’.[22] It is this pillar which represents the cooperative relationship between Army and the society from which it is drawn and which it serves. Within extant military profession discourse, jurisdiction is closely related to Huntington’s concept of ‘responsibility’, namely the use of skills and expertise in a manner that benefits society rather than the individual. The concept of jurisdiction does, however, differ in that Huntington saw ‘responsibility’ as being the burden only of officers, whereas to Stuart it permeates across all members of the Army.[23] It is erroneous to consider that this pillar is merely a rebranding of civil-military discourse; it goes far beyond that to also include concepts such as social and legal legitimacy, social licence, Army’s interactions with the community, and public perceptions of Army’s role and purpose. As Sam C Sarkesian stated in 1975, ‘the military cannot bestow legitimacy upon itself’, and ‘only when society feels that the military institution and the profession are representative of society, and are responsive and accountable to it … [can it] achieve a high degree of legitimacy and credibility’.[24] Maintaining a relationship with its client and undertaking its tasks in accordance with social expectations is critical for a profession’s existence; failure to do so forces clients to take their problems to someone who will.[25]

Among the three pillars of the Army profession, that of ‘expertise’ is the most self-explanatory. As Abbott has argued, professions are the means through which industrialised societies structure expertise.[26] Army’s capacity to maintain and develop new knowledge is not only fundamental to its status as a profession but also ‘central to our ability to fight and win’.[27] Army personnel are expected to be the masters of their field. This is only natural:

Just as a client wants a lawyer who has kept up with the latest court decisions, and a patient wants a surgeon who is skilled in the latest techniques, so too a government wants a military that has made every effort to prepare for a phenomenon as deadly, uncertain, and meaningful as war.[28]

Within his addresses on this subject, Stuart has identified a range of challenges Army faces in ensuring its expertise is of the standard and breadth to suit the challenges of the modern strategic environment. These range from providing a stronger foundation of military knowledge to Army’s leaders and enhancing professional military education, through to hardwiring adaptation and innovation into Army’s processes, reoccupying the intellectual space of the profession from external commentators, ensuring the sufficiency of its doctrine, and trying to find an institutional ‘balance’ between technology, futurism, history, philosophy, ethics and strategy.[29] Within this pillar, a critical contemporary and future task for Army is to develop expertise in the operation of a range of new systems currently under acquisition, such as large landing craft and self-propelled howitzers. Army’s ability to generate, maintain and, where necessary, forget its expertise is—and will remain—an enduring challenge.

The third and final pillar identified is that of self-regulation. Stuart has defined this pillar as Army’s ‘ability to uphold professional standards in our conduct, both in peace and war’.[30] Within any professional group there is a need to regulate behaviour to ensure that the institution maintains a positive relationship with its clients and that expertise is applied in an ethical manner. This entails the development and enforcement of a set of ethics and standards of performance, in Janowitz’s formulation.[31] Stuart has further broadened the scope of this concept, noting that this pillar includes consideration of the Army’s ‘virtue ethic’, its ‘philosophy as a fighting force’, its professional culture, its system of command and control, its command accountability, and the ability of its individuals to resist the moral ‘corruption of war’.[32] This represents a litany of considerations, and researchers could spend entire careers investigating each. Military culture, for example, has come to be regarded as an integral part of the study of military professionalism and it alone encompasses a wide array of influences such as discipline, professional ethos, ceremonies, etiquette, esprit de corps, customs, traditions, rituals and cohesion.[33] Soldiers are generally aware that ‘at the heart of their profession lies a set of ethical responsibilities that above all else are functional to their purpose’,[34] but it is an open and pressing question as to how Army’s culture and ability to self-regulate might fare in a conventional conflict in the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, according to one scholar, Army is already tackling new intellectual and moral problems that it ‘is not currently equipped to overcome’.[35]

Lieutenant General Stuart’s formulation of the three pillars of the Army profession offers a useful framework through which Army personnel (both serving and retired), supported by academics and other stakeholders, can investigate the unique nature and characteristics of the profession in an Australian context. There is a long road ahead in this area of introspection—the surface has only been scratched. As a topic, its breadth and depth militate against easy formulations, conclusions or solutions. Just as an army requires a theory of an army,[36] so too does the Australian Army profession require a theory of the profession to ensure it remains a world-class capability that serves the needs of society. Development of such a theory should be led by Army’s professionals, for it is their responsibility to ‘reflect deeply and with scholarly detachment about the needs of their own institution and its claims for social support’.[37] If it chooses to not engage in such a critical discussion, Army will suffer and it may find its legitimacy and standing with society so eroded that it becomes impossible to achieve its objectives in the defence of Australia and its interests.[38]

State of the Army Profession—Australian Army Journal

It is with this context in mind that I am pleased to introduce this latest edition of the Australian Army Journal, the longest-running military journal in Australia. Since 2023, the Australian Army Research Centre (AARC) has sought to maximise its service to Army through the publication of an annual themed edition of the journal on a key Army research priority, introduced by the AARC’s lead researcher for that topic.[39] In line with Lieutenant General Stuart’s direction that there be a focus in 2025 on reviewing the state of the Army profession, the AARC called for the submission of papers on the topic, including soliciting a range of contributions from individuals internal and external to Defence. In response, we have been pleased to receive a range of thought-provoking papers on two pillars of the profession: expertise and self-regulation.[40]

In his article David Stahel, a renowned expert on the Eastern Front in the Second World War, explores the unique German origins of Auftragstaktik, or ‘mission command’. As Stahel notes, the origin and a concise definition of the concept is difficult to pin down and, contrary to common perceptions, mission command was unevenly practised by the German Army in the First and Second World Wars. Yet it is a concept that has been widely adopted by many Western militaries in recent decades, including by the Australian Army. From the intellectual baseline on mission command provided by Stahel, several contributors have provided ‘response pieces’ to discuss the concept in relation to contemporary Army challenges. In his response, noted historian and national security expert John Blaxland has contributed a history of Army’s association with the concept to the early 2000s. Dayton McCarthy, meanwhile, has explored the relevance of mission command (or lack thereof) to domestic security and response operations. In his response, Anthony Duus suggests that mission command is not just a method of command but the Army’s usual practice, though it cannot be taken for granted and depends on building trust between superior and subordinates. While variations exist throughout Army, views differ significantly between services regarding the theory and practice of mission command. This reality can prove problematic in integrated commands. Addressing this, in their article, Alistair Cooper and Felicity Petrie explore the relationship between mission command and the concept of command by veto—a useful analysis for any Army or Navy member working within the joint environment. As a final response piece, Andrew Sharpe, retired British Army Major General and currently Director of the UK’s Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research, has provided some views on mission command in the British Army, a key AUKUS partner.

A further seven articles are included in this edition. Michael Krause, author of ADF-I-5 Decision-Making and Planning Processes (2024), not only provides a brief history of military planning and planning processes in the Australian Army but also offers a deeper understanding of the thinking that lies at the heart of it. In their contribution, Marigold Black and Michael Webster explore a little-studied aspect of warfare: the rapid development and integration of stopgap weapons, and how this relates to an army’s ability to innovate and adapt while in contact. In a further contribution touching on the Army’s expertise in planning, Aaron Jackson analyses the unique nature of Decision-Making and Planning Processes doctrine, providing considerations as to how these processes can be further enhanced. In ‘Developing the Army Mind’, Chris Wooding explores current approaches to teaching Defence mastery to ADF junior officers, and reforms to be considered to better enhance their intellectual edge and prepare them for the challenges of today and tomorrow. In his article, Charles Miller explores modern perspectives on the wide body of innovation studies literature. Through assessing the merits and strengths of different viewpoints, Miller links their prospective value to the state of the military profession in Australia. That the Army requires personnel who are committed to ethical and moral conduct cannot be disputed. Therefore, Renton McRae and Darren Cronshaw argue, in order to prepare for future challenges, Army needs to develop a moral framework to guide the actions of its professionals. Finally, contestability is essential to all matters of empirical knowledge. Concepts and perceptions must be routinely questioned and re-evaluated in light of changing context. In his contribution, Philip Hoglin places his head above the proverbial parapet and asks an important question: does the profession of arms actually exist? It is a first-principles enquiry that should undoubtedly be the source of more discussion and debate.

This ‘State of the Army Profession’ edition also contains several other valuable contributions. In his standalone essay, Nicholas Bosio provides a contemporary review of Morris Janowitz’s The Professional Soldier. A key text in the study of the military professions, Janowitz’s book is still in use internationally. As it is a 65-year-old work—and one written for the unique context of the US during the Cold War—Bosio rightfully questions the degree to which it should be relied upon in analysing military professionalism in Australia. In 2025, and for the first time in many years, Army held an essay competition. Respondents were asked to provide a 5,000-word (exclusive of citations, +/– 10 per cent) essay, academically written and styled, responding to three questions related to the ongoing review of the Army profession.[41] Some 36 eligible responses were received from throughout Army, Navy, Air Force and the Australian Public Service. These responses were assessed, and we are pleased to publish the winning and runner-up entries here.[42] The Australian Army Journal would not be complete without the inclusion of book reviews. Such reviews provide readers with informed assessment of recent literature published within the fields of military history, security studies, military art and science, highlighting not only these works’ positive qualities but also where they may be lacking. It is with kind thanks, therefore, that we publish here reviews contributed by Matthew Jones, John Nash, Daniel Phelan, Albert Palazzo, Carl Rhodes, Adam Hepworth and Callum Hamilton.

A final word of thanks in this introduction is essential. An academic journal such the Australian Army Journal would not be possible without the time and expertise of its peer reviewers. Such reviewers not only help maintain the high standard of the content published within the journal but often do so in addition to contributing articles or fulfilling their regular roles and duties in the military, the public service, broader government, industry, or the academic community. I am therefore pleased to express the AARC’s gratitude to them: thank you for your contributions to the Australian Army Journal.

Dr Jordan Beavis

Academic Research Officer

Australian Army Research Centre

My deepest thanks to Dr Andrew Richardson, Dr John Nash, Ms Kim Philpot, Ms Luisa Powell and COL Tony Duus for their intellectual and moral support in preparing this introduction. As usual, any intellectual endeavour such as this would not have been possible without the love, support and distractions of Renee Beavis and Cassandra Beavis.

Endnotes

[1] This extends to the idea of a distinctly Australian ‘profession of arms’ which, although discussed within Australian Defence Force Doctrine, has not been explored holistically.

[2] There is perhaps an opportunity for the Chief of Army to direct the AAJ to bear a new such subtitle, potentially either ‘For the Army Profession’ or ‘Journal of the Australian Army Profession’, though the second-order effect this may have on external contributions to the journal would need to be considered.

[3] Craig Wilcox, ‘Colonial Military Forces’, in Peter Denis et al. (eds), The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, 2nd edition (Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 143–145. Various colonial militia or volunteer units were formed in Australia prior to the 1860s, though these wholly comprised non-professionals. If we are to consider the presence of the British Army garrison from 1790 to 1870, and a number of men born or raised in Australia who joined the British Army (as either officers or other ranks) in this period, the lineage could be extended further. See Craig Wilcox, Red Coat Dreaming: How Colonial Australia Embraced the British Army (Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 125–126.

[4] Some of the best regarded include those produced by the Australian Army History Unit through its series with Cambridge University Press.

[5] For an example of the latter, see the Military Organisation and Culture Studies research group at https://militaryculture.org/about/.

[6] Intellectual engagement with the Australian ‘profession of arms’ is more developed than that of the ‘Army profession’. For an early example, see RG Funnell, ‘The Professional Military Officer in Australia: A Direction for the Future’, Defence Force Journal 23 (1980): 23–39. More recently, Professor Michael Evans has sought to foster greater discussion of the profession of arms within Australia. See, for example, Michael Evans, ‘Revival or Decline? The Australian Profession of Arms in the Twenty-First Century’ (presentation), Australian Institute of International Affairs, Canberra, 24 April 2025; Michael Evans, Vincible Ignorance: Reforming Australian Military Education for the Demands of the Twenty-First Century (Department of Defence, 2023); Michael Evans, ‘A Usable Past: A Contemporary Approach to History for the Western Profession of Arms’, Defense and Security Analysis 35, no. 2 (2019): 133–146.

[7] See William Guthrie, A New Geographical, Historical, and Commercial Grammar; and the Present State of the Several Kingdoms of the World (J. Knox, 1771), p. 263.

[8] Charles James, ‘Officer’, A New and Enlarged Military Dictionary, in French and English, Vol. 2, 3rd edition (T. Egerton, Military Library, 1810). Use of the term ‘profession of arms’ in Australia can be traced to as early as 1816. See ‘From the Late London Papers’, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 20 April 1816, p. 2.

[9] William Darby, Mnemonika or the Tablet of Memory (Edward J. Coale, 1829), p. 24.

[10] Ian FW Beckett, A British Profession of Arms: The Politics of Command in the Late Victorian Army (University of Oklahoma Press, 2018), pp. 3–4.

[11] See John Hackett, The Profession of Arms: The 1962 Lees Knowles Lectures, reproduced in The Profession of Arms: Officer’s Call (Center for Military History, 2007); John Hackett, The Profession of Arms (Macmillan, 1983); John Hackett, ‘The Profession of Arms’, Proceedings (United States Naval Institute) 93/4/770 (1967).

[12] OH Becher, ‘The Profession of Arms’, The Canberra Times, 11 June 1968, p. 12; Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defence, ‘Report on the Australian Army’ (Government Printer of Australia, November 1974), available at: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1745313661. My thanks to Ms Hannah Woodford-Smith for alerting me to the existence of the latter source.

[13] Australian Defence Force, ADF-C-0 Australian Military Power, 2nd edition (Department of Defence, 2024), p. 69.

[14] See, for example, ABN Churchill, ‘The Army as a Profession’, The Journal of the Royal United Service Institution LIV, no. 384 (1910): 166–198. It is important to consider that, while published in Britain, the Journal of the Royal United Service Institution circulated widely throughout the British Empire, including in Australia. See Jordan Beavis, ‘A Networked Army: The Australian Military Forces and the other Armies of the Interwar British Commonwealth (1919–1939)’, PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, 2021.

[15] There has also been advocacy in the United States for the development of a ‘Space Profession’ following the creation of the US Space Force. See Bryan M Titus, ‘Establishing a Space Profession within the US Space Force’, Air & Space Power Journal 32, no. 3 (2020): 10–28.

[16] Don M Snider and Gayle L Watkins, ‘Introduction’ in Lloyd J Matthews (ed.), The Future of the Army Profession (McGraw-Hill Primis Custom Publishing, 2002), pp. 6–7.

[17] Meredith Kleykamp has acknowledged Huntington’s and Janowitz’s contributions as the ‘canonical models and theories guiding the understanding of the military profession’ but has also argued that the ‘utility of these foundational works for understanding and managing the modern military profession may be in decline’ owing to significant social and cultural developments in the many years since publication. Meredith Kleykamp, ‘Foreword’, in Krystal K Hachey, Tamir Libel and Waylon H Dean (eds), Rethinking Military Professionalism for the Changing Armed Forces (Springer, 2020), p. vii.

[18] For an examination of this, utilising the framework of the differing roles of universities in educating members of professions in the United States, Britain, France and Germany, see Andrew Abbott, The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor (University of Chicago Press, 1988), pp. 195–211.

[19] See Simon Stuart, ‘The Human Face of Battle and the State of the Army Profession’, speech, Chief of Army Symposium, Melbourne, 12 September 2024, transcript available at: https://www.army.gov.au/news-and-events/speeches-and-transcripts/2024-09-12/chief-army-symposium-keynote-speech-human-face-battle-state-army-profession; Simon Stuart, ‘The Challenges to the Australian Army Profession’, speech, National Security College, Australian National University, Canberra, 25 November 2024, transcript available at: https://www.army.gov.au/news-and-events/speeches-and-transcripts/2024-11-25/challenges-australian-army-profession; Simon Stuart, ‘Strengthening the Australian Army Profession’, speech, Lowy Institute, Sydney, 3 April 2025, transcript available at: https://www.army.gov.au/news-and-events/speeches-and-transcripts/2025-04-03/strengthening-australian-army-profession.

[20] Italics in original. Australian Army, The Australian Contribution to the National Defence Strategy (Australian Army, 2024), p. 1. It should also be noted that Army continually provides substantial contributions to wider Defence operations. Significant numbers of Army personnel are employed in Vice Chief of the Defence Force Group, Joint Operations Command, Joint Capabilities Group, Defence People Group, Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, Defence Intelligence Group, Defence Science and Technology Group, Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance Group, and Strategy, Policy and Industry Group, while Army also provides a range of secondees to other government departments.

[21] Stuart, ‘The Challenges to the Australian Army Profession’. Stuart’s first conceptualisation of this pillar was entitled ‘service to society’; see Stuart, ‘The Human Face of Battle’.

[22] James Burk, ‘Expertise, Jurisdiction, and Legitimacy of the Military Profession’, in Lloyd J Matthews (ed.), The Future of the Army Profession (McGraw-Hill Primis Custom Publishing, 2002), p. 21. For Abbott’s introduction of the concept of professional jurisdiction, see Abbott, The System of Professions.

[23] Samuel P Huntington, The Soldier and the State (Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1957), p. 15.

[24] Sam C Sarkesian, The Professional Army Officer in a Changing Society (Nelson-Hall Publishers, 1975), p. 241.

[25] Abbott, The System of Professions, p. 48.

[26] Ibid., p. 323.

[27] Stuart, ‘Strengthening the Australian Army Profession’.

[28] Richard H Kohn, ‘First Priorities in Military Professionalism’, Orbis 57, no. 3 (2013): 388–389.

[29] Stuart, ‘The Human Face of Battle’; Stuart, ‘The Challenges to the Australian Army Profession’; Stuart, ‘Strengthening the Australian Army Profession’.

[30] Stuart, ‘Strengthening the Australian Army Profession’.

[31] Morris Janowitz, The Professional Soldier: A Social and Political Portrait (Free Press, 2017), p. 6.

[32] ‘Stuart, ‘The Human Face of Battle’; Stuart, ‘The Challenges to the Australian Army Profession’.

[33] Krystal K Hachey, ‘Rethinking Military Professionalism: Considering Culture and Gender’, in Krystal K Hachey, Tamir Libel and Waylon H Dean (eds), Rethinking Military Professionalism for the Changing Armed Forces (Springer, 2020), pp. 4–5.

[34] Kohn, ‘First Priorities in Military Professionalism’, p. 381.

[35] Benjamin Gray, ‘Aristotelian Battle Ethics: An Examination of the Utility of Aristotelian Virtue Ethics for the Australian Army at the Tactical Level of War’, Masters thesis, UNSW Canberra, 2025, p. 10.

[36] Stuart, ‘Strengthening the Australian Army Profession’.

[37] James Burk, ‘Thinking Through the End of the Cold War’, in James Burk (ed.), The Military in New Times: Adapting Armed Forces to a Turbulent World (Routledge, 1994), p. 14.

[38] As Abbott has clearly indicated within his research, a profession’s inability to satisfy the requirements of its client, or its inability to adapt as context (technology, social and cultural values) changes can see its failure, degradation or annexation by a competing profession. See Abbott, The System of Professions.

[39] Dr John Nash provided the first such introduction to a themed edition of the Australian Army Journal in a littoral manoeuvre themed edition in 2023, while Ms Hannah Woodford-Smith penned the introduction to the 2024 themed edition on ‘mobilisation’. See John Nash, ‘AAJ Littoral Manoeuvre Collection’, Australian Army Journal XIX, no. 2 (2023): vii–xvi; Hannah Woodford-Smith, ‘Introduction’, Australian Army Journal XX, no. 3 (2024): 5–14.

[40] No articles were submitted for consideration on the jurisdiction pillar.

[41] These were: Q1. How can the Army, as a profession, be optimised for littoral warfare operations? Q2. How can the Army, as a profession, enable rapid mobilisation and expansion for conflict, if required? Q3. How can the Army, as a profession, fully and effectively contribute to the ADF’s Integrated Force?

[42] A collection of top-ranking essays submitted to the competition will be published by the AARC in due course.