The Utility of Mission Command within Domestic Security and Response Operations

The land domain is where people live, where decision makers reside and where human, physical and technical access to all other domains begins. It is where military action intersects with populations and audiences. It encompasses decisive terrain and hosts critical infrastructure.[1]

Domestic operations have unique characteristics and considerations.[2]

Introduction

Associate Professor David Stahel’s ‘Auftragstaktik: The Prussian-German Origins and Application of Mission Command’ provides a nuanced assessment of a concept that has been widely adopted by most Western armies.[3] Indeed, the concept of Auftragstaktik—better known in such armies by its more prosaic-sounding English translation of ‘mission command’—occupies an exalted status within doctrine and military theory. Stahel acknowledges this up front and so proceeds immediately to describe the historical underpinnings of the concept. In doing so, he demonstrates that, far from being universally adopted within the Prussian and later German armies, the concept was understood and implemented in varied ways—if it was adopted at all. Stahel posits that there was no ‘golden age’ of Auftragstaktik.

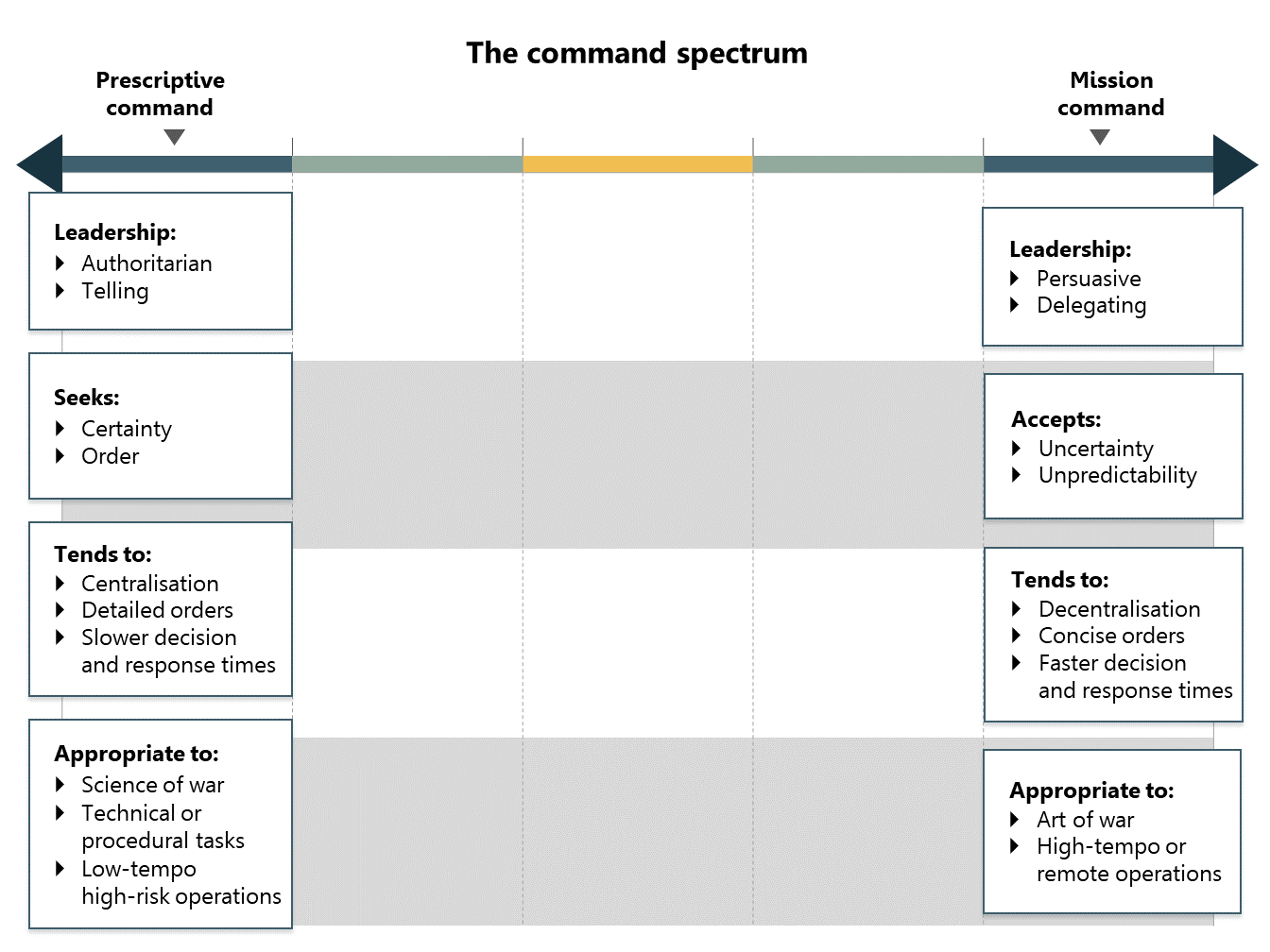

In spite of this, mission command has been adopted by the Australian Defence Force (ADF) as the preferred command model. ADF-P-0 Command, which also takes a very nuanced approach to mission command, states that while there will be occasion for the use of ‘prescriptive command’, the ADF has a ‘bias’ for mission command. Nonetheless ADF-P-0 Command cautions that the chosen command approach ‘will depend on a variety of factors, such as the nature of the mission, the nature and capabilities of the adversary and perhaps most of all, the qualities of our people’.[4] This is an important caveat. Although the concepts of employment, doctrine and standard operating procedures are in a developing state as they apply to domestic security and response operations, we can be still certain of several things.[5] The first is that such operations will be characterised by complexity due to the need to synchronise and integrate with whole-of-government and interagency partners. But working against this is a lack of trust born from poor interoperability and differences in organisational cultures among the agencies supported by the ADF on such operations.[6] The second will be the imposition of restrictive rules of engagement (ROE). The third, especially in the absence of a declared conflict (i.e. ‘grey zone warfare’) and without expanded ADF authorities, will be ever-present political sensitivities to military operations on Australian soil. The fourth, which is related to the third, is that domestic security and response operations will inevitably have strategic effects. For example, if a soldier miscalculates, overreaches their authority or, alternatively, is perceived to have responded inadequately, these deficiencies can be readily ‘weaponised’ by malicious actors.[7] Taken together, these considerations would suggest that although the ADF’s preferred ‘bias’ is for mission command, something akin to ‘prescriptive command’ is, in the words of ADF-P-0 Command, not only ‘appropriate’ but also ‘necessary’.[8]

This article will discuss the applicability of mission command to domestic security and response operations. To do so, it will first examine key aspects of Stahel’s article, drawing out certain themes that relate to the applicability—or otherwise—of this command concept to domestic security and response operations. Next it will examine the strategic guidance given to Army and how this has guided the development of military security and response operational concepts and draft doctrine. Such concepts and doctrine have also been informed by recent ADF exercises as well as an examination of historical precedents. Therefore, while concepts and doctrine are in the developing and draft stage, there is sufficient material available to assess the utility of mission command to domestic security and response operations.

‘A constant state of tension’—a Precis of the Concept

Stahel, a German speaker, has researched key German-language sources. This provides crucial context to the concept that has been distilled (or perhaps even lost) over time. This historical background provides some good insights, none more so than that Auftragstaktik was not an unimpeachable idée fixe in the Prussian/German tradition. Does this contested provenance undermine the concept, noting that much of the basis for its adoption in the postwar Western armies was due to the supposed battlefield advantages it bestowed upon the German Army in the Second World War?

The answer to this question is ‘possibly’. Stahel makes it clear that, even among its earliest Prussian advocates, Auftragstaktik was not intended to be a carte blanche empowerment of subordinate officers working only loosely within a broad strategic intent. ‘Prussian officers’, observes Stahel, ‘were not free spirits making their own choices [as] their training traditions, and insular culture predetermined much of their thinking, leaving a relatively narrow scope for discretionary behaviour’ (emphasis added).[9] Opposing the concept were the ‘normal tacticians’, who believed that modern warfare required precision, coordination and synchronisation of formations and fires. ‘Normal tacticians’ could not abide any concept that threatened the intricate workings of the cohesive whole of an army on the battlefield.[10]

Stahel then overlays another much-lauded Prussian-originated concept—the Clausewitzian world view. With war understood as something that could not be controlled but was rather a phenomenon characterised by chaos, friction and chance, Clausewitz and his later proponents stressed that military thinking must react and adapt to war’s vagaries, including the loss or degradation of the means of command and control. This, therefore, placed a premium on Auftragstaktik, which was seen as an ‘organic solution [of] a culture of instinctive initiative and rapid intervention’ that could ‘counteract the inevitable gridlock of otherwise rigid command processes and battlefield confusion’.[11] With Auftragstaktik infusing the command culture of the Prussian and later German armies, it was believed that it was better to make an incorrect decision than to make no decision at all.

With some evidence suggesting that Auftragstaktik was barely applied at the tactical level but wholeheartedly adopted (and often abused) at the operational level in the German Army of the Second World War, Stahel reparses the admonitions of the ‘normal tacticians’ who warned against ‘exaggerating the principle of independence into an absolute law’. Instead, Stahel notes, such officers stressed the ‘importance of the situation, which could make it necessary to restrict the subordinate leaders’ scope for action’ (emphasis added). And so, with the historical context in place, Stahel concludes that there never was a universally adopted or understood Auftragstaktik. Instead, he writes:

The best that might be said is that Auftragstaktik is in a constant state of tension, oscillating according to battlefield circumstance, the level of command, available communication technologies and the willingness of personalities or command cultures to act or instruct.[12]

As a coda, Stahel ruminates on the dangers of adopting a concept without a clear understanding of the specific historical and cultural contexts from which it was born. Here he brings his interesting foray into the history of Auftragstaktik into the spotlight for the contemporary Australian military professional. For the Germans, Auftragstaktik was nothing more than the most efficient means to achieve a military end. Stahel describes this perspective as being ‘functional-rational’; this is also known as ‘instrumental rationality’.[13] But for the ADF, like many other Western militaries, mission command has evolved into something more. Specifically, mission command has been adopted not just for its perceived functional benefits but also on the basis of the value-rational benefit it offers—regardless of whether the original intention of mission command was to do so. Value rationality refers to making decisions based on a series of values; that is, the importance of adhering to these values is correct and good in and of itself. Specifically for the ADF, value rationality is built on ethical, legal, political and social aspects that are deemed appropriate for the practice of command and leadership of military forces in a democracy. As ADF-P-0 Command notes, because ‘mission command decentralises decision-making authority, and grants subordinates significant freedom of action, it demands more of commanders at all levels and requires extensive training and education’ (emphasis added).[14] In other words, in the ADF, mission command can exist only when there is sufficient trust between superior and subordinate. For the superior, this is the trust that the subordinate will make not only the ‘best’ decision (instrumental rational) but also the ‘right’ decision (value rational). Trust—the grease that lubricates the cogs of mission command—must be grown formally through education and training and informally through relationships, experience and immersion in the organisation.

Thus, one may observe that several elements in this precis require further examination. These elements suggest that prima facie mission command may not be suitable for security and response operations. Alternatively, if mission command is suitable, what preconditions would need to be met? To answer this, one must understand the strategic and the operational context of such operations and the factors that may preclude the practice of mission command in domestic security and response operations.

Domestic Security and Response Operations—a Work in Progress

What, then, are domestic security and response operations? The Defence Strategic Review provides this explicit but broad guidance:

[E]nhanced domestic security and response Army Reserve brigades will be required to provide area security to the northern base network and other critical infrastructure, as well as providing an expansion base and follow-on forces.[15]

From here, the National Defence Strategy gives more detailed direction. It states that the primary mission of the ADF is to defend Australia through the strategy of deterrence by denial. A key element of this is ‘a logistically networked and resilient set of bases, predominantly across the north of Australia’. Accordingly the ADF’s ‘ability to protect its personnel, critical facilities and information in Australia underpins its ability to defend Australia, project force and hold the forces of any potential adversary at risk’.[16]

The ‘how’ of base and infrastructure security is then woven through, and nested within, the ADF Joint Concepts Framework. This starts with the capstone concept of Concept APEX: Integrated Campaigning for Deterrence and is further refined into Concept ASPIRE, which details the theatre missions, most notably Theatre Mission One—Defend Australia.[17] Beneath this is Concept Lantana—the Land Domain Concept, which clarifies further that:

the land force contributes to domestic support, domestic security and homeland security in conjunction with the integrated force and in partnership with national and state authorities and coalition force elements. It contributes to situational awareness across Australia’s north alongside all-domain sensors, and delivers protection of northern base network and critical infrastructure. It enables the integrated force through security of coalition and joint force assets.[18]

Finally, The Australian Army Contribution to the National Defence Strategy identifies the ‘who’. It states that the 2nd (Australian) Division will be responsible for ‘domestic security and response operations’ which support ‘civil authorities with homeland security including the northern base network and other critical infrastructure’.[19] Joint Task Force 629 (JTF 629), based upon the 2nd (Australian) Division, is the standing JTF responsible for domestic operations, including Defence assistance to the civilian community (DACC) and Defence Force aid to the civil authorities (DFACA) in addition to homeland defence tasks detailed above. Within JTF 629 reside several subordinate joint task groups (JTGs) which are generated from the state-based brigades of the 2nd (Australian) Division.

Although security and response operations, within the context of homeland defence, will be joint and interagency, there is a very clear focus on land forces, and the 2nd (Australian) Division in particular. In other words, domestic security and response operations will be a key part of the land force’s contribution to the integrated force. To this end, the Army commissioned the Land Contributions to Homeland Defence Concept of Employment as a starting point from which to develop force structures, capabilities, plans and subordinate doctrine. This concept of employment (CONEMP) is subordinate to Concept Lantana. It sets the scene quickly when describing the homeland operating environment as:

a complex array of stakeholders requiring close coordination between agencies with overlapping authorities and responsibilities. Effective planning and execution requires a unified approach through a national coordination mechanism. These challenges are compounded by vast geographical dispersion and a paucity of security resources across all agencies. The number of vulnerable assets and infrastructure far exceed the number of forces available for protection operations.[20]

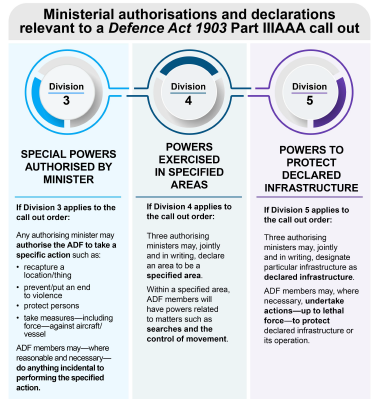

Expanding upon this further, the CONEMP acknowledges three key aspects. The first is that civil authorities will retain primacy for policing and security within state and territory jurisdictions. In other words, state and territory boundaries and equities do not simply disappear when security and response operations are to be conducted.[21] The second is that deployment of armed ADF elements domestically requires specific legal authority; such authority may be derived from extant legislation—the Defence Act 1903—or from within the executive power inherent in the Constitution. The Defence Act Part IIIAAA provides for ministerial authorisation for use of the ADF within Australia for specific purposes up to and including the use of lethal force. The three authorisations are shown in Figure 1.

Source: ADF-I-3 Domestic Operations, p. 44[22]

If the ADF is called out under these authorities, the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) is permitted to use the ADF to exercise specific powers. Part of the orders issued by the CDF will be specific ROE for the operation. Even with these authorisations under the Defence Act, however, the scope of the ADF’s role is not entirely clear. Specifically, these authorisations relate to ‘domestic violence’ as it relates to DFACA rather than the envisaged security and response operations in time of conflict. One may assume that in time of war the Australian Government might exercise its executive power to widen the employment of, and the authorities given to, the ADF. Despite the existence of such provisions in the Defence Act, use of the ADF within Australia for the purpose of internal security operations remains a contentious area of constitutional jurisprudence.[23] Legal and jurisdictional concerns are likely to be an ever-present characteristic of security and response operations. Therefore, the legal officer will likely be one of the key members of any JTG or JTF staff.

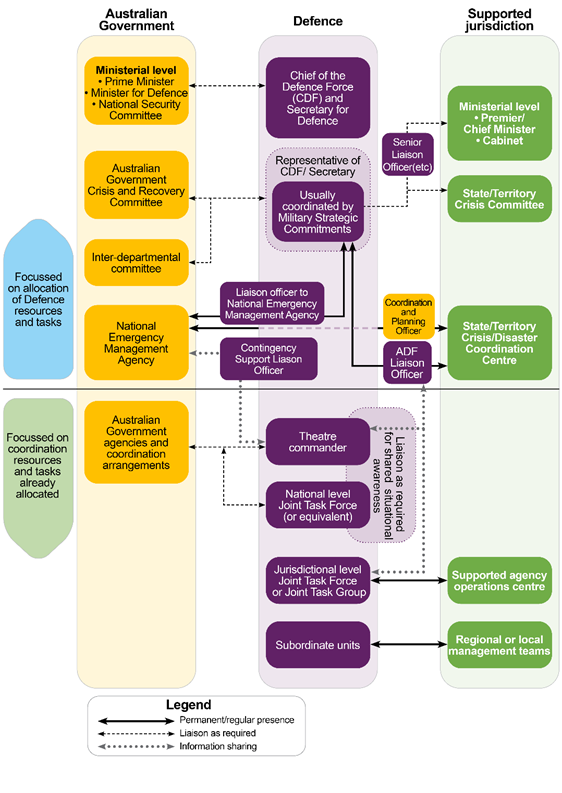

Security and response operations will be interagency in nature, comprising both state and federal entities, and straddling state and territory jurisdictions. This makes a national coordination mechanism necessary to support coordination and assist in reconciling competing priorities for the use of the ADF. Such coordination will take place at the strategic, operational/national, state/tactical and local/sub-tactical levels of command.

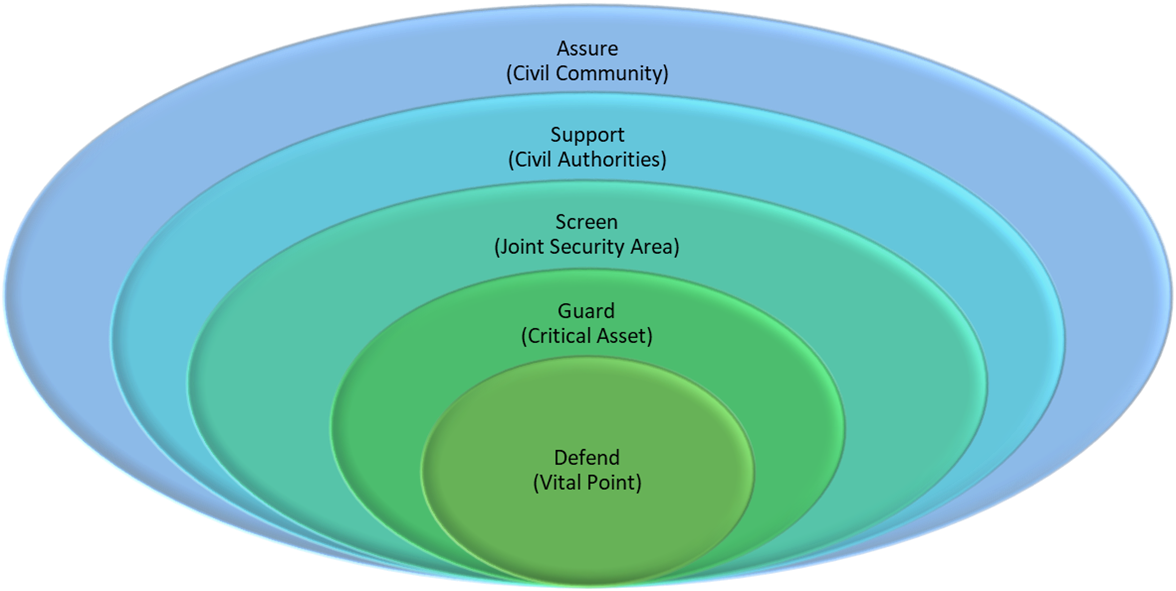

Within the legal, jurisdictional and interagency context of this framework, the CONEMP describes the land force effects within homeland defence. Broadly, such effects may be characterised in terms of three operational functions: ‘detect’, ‘protect’ and ‘respond’. These functions are part of standardised language understood by the military as conveying specific actions or tasks to be performed. These include, for example, defence of vital points, wide area surveillance (such as that conducted by the Regional Force Surveillance Group), wide area security, and support to prisoner of war, internee and detainee (PWID) operations.[24] Even in crisis or conflict, the requirement to support DFACA and DACC exists in parallel.

Examples of land force effects can be broken down further into missions or tactical tasks. For example, ‘wide area security’ entails the protection of populations, forces, infrastructure and activities to deny the enemy positions of advantage. Tactical tasks will include patrol, clear, seize, attack, defend, destroy, capture/detain, cordon and search, as well as the conduct of information activities. For the protection of critical assests, land forces may employ graduated force up to and including lethal force against threats and intrusions to protect, defend, retain or secure critical assets, designated infrastructure or prescribed areas. Related actions may include screen and guard patrolling; the establishment of checkpoints, access control and cordons; and the conduct of decisive engagement to deter, repel and defeat hostile acts.[25] Some of the protective tasks could be conducted to protect Royal Australian Air Force or Royal Australian Navy bases. This possibility necessitates that a clear understanding exists among the three services of the relevant command relationships and responsibilities of both the ‘protected’ and the ‘protector’. Such tasks may also be conducted in conjunction with civilian police. Remember also that these actions will take place on Australian soil, potentially in and around Australian cities and towns and, most notably, could potentially be conducted against Australian citizens or residents. Australian and international media will be present. Likewise, we may assume that ‘citizen journalists’—some with malicious intent—will be recording and posting the actions of security and response forces on social media. If the captured media is not controversial enough, we may assume that some actors will produce AI-enabled ‘deepfakes’ to create media that supports their particular narrative.

With the CONEMP in place, there are several concurrent lines of activity conducted by Army (particularly 2nd (Australian) Division) that seek to broaden and deepen the collective understanding of security and response operations. This includes assimilating lessons from relevant command post and field training exercises, modernising and then testing ‘Defence of Australia’ era dormant doctrine, and analysing force structure concepts through wargaming and experimentation. Understanding the totality of, and the multitudinous tasks and linkages within, security and response operations is ongoing: it is a work in progress. What one may see, however, is the manifold mix of interagency challenges, political sensitivities, legal ambiguity and competing demands for finite capabilities. One associated challenge is how to apply mission command within this context.

The Challenge—Balancing Independence and Compliance

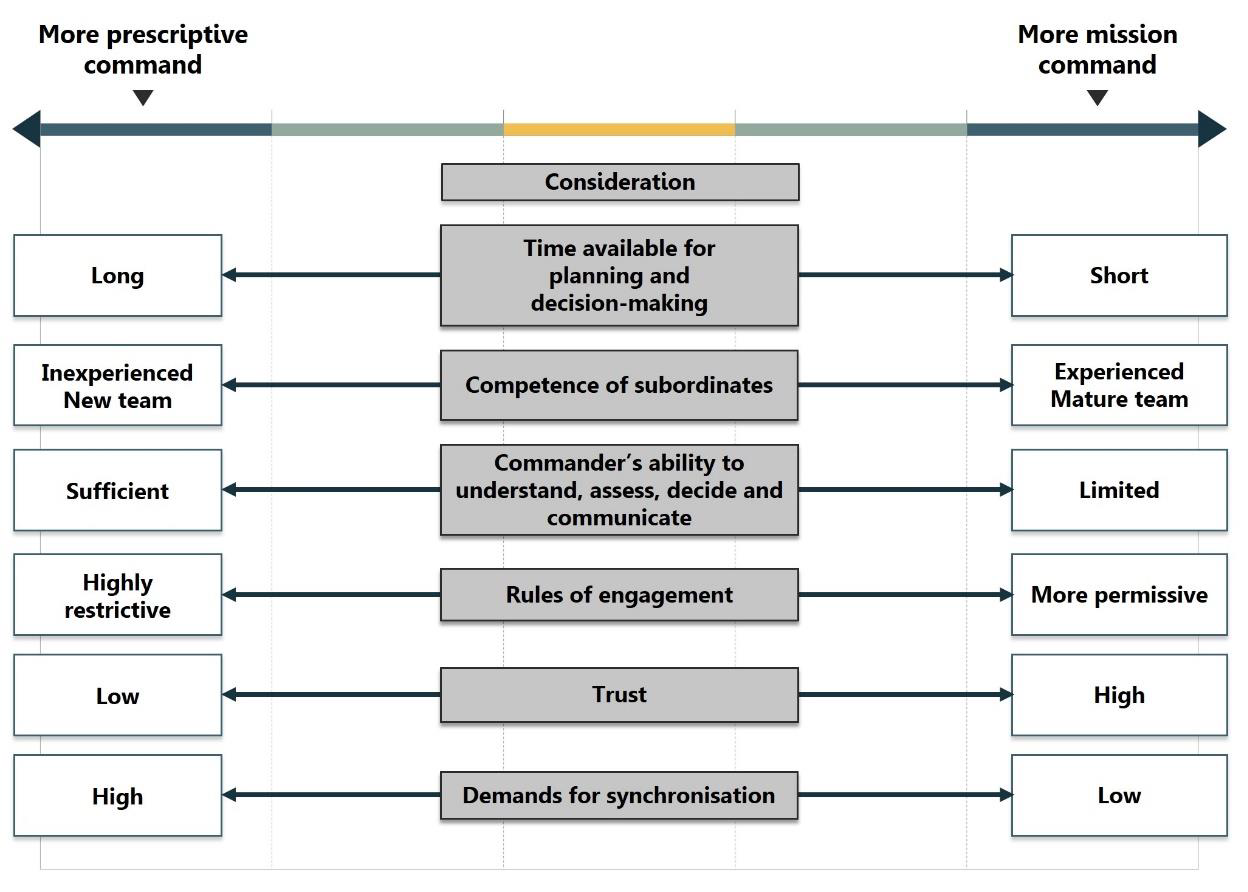

ADF-P-0 Command states that ‘command exists on a spectrum … with prescriptive command at one end and mission command at the other’. In prescriptive command, commanders produce detailed plans and coordination arrangements. The successful execution of these plans requires strict compliance with the details, and thus subordinates’ freedom of action must be minimised. Information is fed to the top of the chain of command where the decision-making authority lies; orders are then issued downwards for execution. ADF-P-0 Command concludes that ‘organisations that are characterised by distrust tend towards it’.[26] The spectrum of command is illustrated in Figure 4.

Based on what this article has illustrated thus far, one may assess that the characteristics of security and response operations strongly favour prescriptive command. This is because of the centralised nature of the top-down coordination framework—a framework designed to facilitate state and federal government and interagency objectives, actions and information sharing (which the ADF must plug into at all levels). By virtue of legal necessity, several security and response tasks will be very procedural and technical in nature, and must be executed prescriptively. PWID operations, overseen by an array of international treaties and federal and state laws, are the best example of such tasks.[27] But even the relatively simple act of providing an armed patrol within an Australian town will be technical and procedural insofar as that it must comply with state and federal laws, CDF directives and ROE.

Based on these considerations, one might conclude that prescriptive command, far from being a less than ideal command style, actually protects security and response forces in an armour of well-planned legality and coordination. The reality is that failure to follow relevant laws and directions may endanger soldiers and civilians alike, and may also result in negative public perceptions of the military. In such circumstances, prescriptive command may offer the best means to ensure that security and response forces achieve the strategic intent of the mission. While we observed that the legal officer will be a key player in the security and response operations, it may be equally assumed that the public affairs officer and those charged with conducting information actions will also be critical capabilities for such operations.[28]

As previously mentioned, a major factor affecting the conduct of security and response operations will be the need to work effectively with state and federal police forces. This may take several forms, from the establishment of a joint police/military framework, to the conduct of joint patrolling, to the sharing of situational awareness at military/police operations centres. In terms of the latter, there have been advances in joint ADF/police interoperability over the last decade. This has largely occurred with respect to DACC responses to a series of fires, floods and COVID-19 operations. The establishment of the ADF’s JTF 629 and the standing state-based military JTGs has enabled these commands to develop ongoing relationships with emergency service and interagency peers.

While the frameworks for cooperation have improved for DACC operations, it is arguable that sufficient levels of interoperability and cross-cultural understanding do not yet exist for DFACA and homeland defence missions. Figure 5 illustrates that low trust normally results in prescriptive command. In the context of land-based security and response operations, trust must exist between Army and the various state and federal police forces. ADF-P-0 Command notes:

mutual trust is the result of shared confidence across an organisation. It is based on the confidence that the group has in each member’s reliability and their competence to perform assigned tasks.[29]

In other words, Army and police must understand each other’s cultures and capabilities (i.e. what each can and cannot do). Despite ostensible similarities between Army and state and federal police—uniforms, badges of rank and several joint DACC responses—it is safe to suggest that Army is still better able to integrate with a foreign military than with an Australian domestic police force. Much of this circumstance arises from the fundamental differences between how Army and police forces ‘do business’:

Military operations are typically proactive and conducted as a unit or team. They are usually carefully considered, planned and controlled according to doctrine. Risk is mitigated through written orders and formal orders groups, stringent control measures and tactical guidance, strict tiered use of force criteria, established ‘actions on’ and rehearsals—all underpinned by limits to soldier discretion within the framework of the ‘Commander’s Intent’.

In comparison, police work is ordinarily highly reactive in nature and conducted individually or in pairs. Police follow broad strategic guidelines too, but the core community policing role revolves around response and individual discretion. When attending an incident individual police officers must make fast decisions, often under pressure, to effectively and appropriately address whatever incident they meet. While supported by training and experience, police must quickly consider a wide array of variables and choose the most suitable options (including use of force) depending on the situation. The time critical nature of these decisions means they are often made in isolation, without further reference to the chain of command.[30] (emphasis added)

From these observations, it is apparent that Army and police have mutually exclusive modi operandi—a situation which does not bode well for security and response operations where Army/police interoperability on the ground (rather than just at the command centre) will be the true test.

To say that barriers exist to the ADF collaborating with police on domestic operations does not mean that mission command has no place. During security and response operations conducted in Australia’s remote north, for example, military units and sub-units will inevitably work dispersed across vast areas. In these situations, maintaining communications will be problematic even in the best of circumstances. Being dislocated both functionally and geographically, units will operate in a disrupted, disconnected, intermittent and low-bandwidth (DDIL) environment. In such scenarios, mission command arrangements would (by the criteria provided in ADF-P-0 Command) remain suitable.

What is more, Stahel makes an interesting observation in the conclusion to his article. He suggests that mission command, as adopted and understood by modern militaries, is infused with value rationality—that is, ‘doing the right thing’. That is not to suggest that instrumental rationality—that is, ‘doing that which best achieves the mission’—has been completely subsumed by it. Instead, it is more accurate to say that the modern understanding of mission command has moved from a purely instrumental-rational system (as originally conceived) to one that has been moderated by value-rational thinking. This conclusion is certainly reinforced by the contents of ADF-P-0 Command and ADF-P-0 Leadership, which combine instrumental and value-rational elements as the command ideal. For example, when discussing mission command, ADF-P-0 Leadership emphasises the primacy of instrumental rationality:

Central to mission command is an understanding that the mission has primacy over all other direction and tasks. The core component of any mission is the purpose—which lays out what is to be achieved and why. Clear articulation of the purpose and the mission enables subordinates to adapt and respond to changing circumstances and uncertain environments.[31]

However, this is not ‘a blank cheque’.[32] ADF-P-0 Leadership cautions that value rationality is a very important element of mission command: ‘Of course, doing the right thing remains paramount. Failure due to negligence should neither be accepted nor overlooked.’[33]

Accepting that value-rational infused mission command exists, what does it offer the modern military? One may suggest that the quality of value rationality imposes a clear restraining effect on the potential excesses of mission command. In other words, instead of the Prussian ideal of bold leadership (where passivity was considered worse than an incorrect decision), the Australian ideal of mission command stresses that a decision cannot be considered ‘correct’ if it does not include doing ‘the right thing’. In the security and response context, the Prussian ideal could be fraught with danger and prone to generate any number of adverse second- and third-order effects. In some circumstances, making no decision may in fact be the lesser of two evils. But making a decision is still the objective. Here, values-infused mission command (wherein several legal, cultural and moral as well as utilitarian factors remove or at least ameliorate the chance of adverse effects) seems well suited to domestic security and response operations. Even with this values-infused mission command, commanders must still issue clear guidance for subordinates. Importantly subordinates at the tactical level must still exercise sound judgement to achieve the mission and reduce the myriad inherent risks that inevitably arise during the conduct of security and response operations.

Mission Command in Security and Response Operations—Yes or No?

Based on the arguments presented in this essay, it would seem that mission command—even with its value-rational additions—is a poor fit for the circumstances inherent in domestic security and response operations. What is more, it is unlikely that any of the structural elements that shape the conduct of such operations (e.g. centralised interagency coordination; stringent legal and jurisdictional parameters; intense community, political and media scrutiny; and the need to work with culturally disparate organisations) can be sufficiently modified to support the exercise of mission command by the military in a domestic setting.

Despite these limitations, there nevertheless remain circumstances where the principle of mission command has clear application. For example, in a situation in which units and sub-units are dispersed, it is difficult to imagine how operations could be conducted without some form of mission command. Equally, if sufficient authorities are allocated to subordinate elements, accompanied by clear ROE, Army units can be more responsive to local police operations and thereby provide far superior security and response effects. Likewise, there are circumstances in which commanders (at all levels) need to apply the principles of mission command in order to coordinate effectively with interagency partners and government representatives. After all, if the tempo of a security or response operation were to become anything other than ‘low’, it is likely that the constraints of prescriptive command would quickly overwhelm headquarters staff.

Whatever the circumstance, questions will inevitably arise as to whether the potential benefit of agile decision-making and response (enabled by the principle of mission command) is sufficient to outweigh the considerable risks to the ADF’s reputation and mission if ‘incorrect’ decisions are made. This is particularly the case in domestic and security operations when the eyes of the nation will likely be firmly focused on the military. Despite this uncertainty, however, the achievement of either prescriptive command or mission command will always depend on adequate training and education among soldiers and junior leaders. This is the only way to ensure that our military men and women are adequately equipped on domestic security operations to protect themselves, essential infrastructure and assets, and the Australian population.

In sum, there is still much to learn about the utility of mission command in the context of security and response operations. The nuances that arise from the unique and challenging context of these operations mean that questions around how best to achieve command are difficult to answer. We can, however, say with some certainty that mission command’s applicability to these operations will be—like Stahel’s assessment of the German military’s engagement with Auftragstaktik—‘anything but simple and clear cut’.

Author’s Note. The author would like to thank Brigadier Rob Calhoun DSC, Brigadier Richard Peace, Colonel Mark Smith CSC, Colonel Rob Lang DSC, Colonel Scott D’Rozario, Lieutenant Colonel Tim Dawe, Lieutenant Colonel Paul O’Donnell and Major Jeremy Barraclough for their thoughts and inputs into this essay. As always, any errors of fact or logic remain the sole responsibility of the author.

Endnotes

[1] Joint Warfare Development Branch, Concept Lantana—the Land Domain Concept, ADF Domain Concept (2024), p. 4.

[2] Doctrine Directorate, ADF-I-3 Domestic Operations, p. 1.

[3] David Stahel, ‘Auftragstaktik: The Prussian-German Origins and Application of Mission Command’, Australian Army Journal XXI, no. 3 (2025). The adoption of mission command for the ADF is also mirrored in Chapter Five of ADF-P-0 Leadership.

[4] ADF-P-0 Command, p. 24.

[5] For example, see ADF I-3 Domestic Operations, p. 1. This publication details the nuances, context and issues of all types of domestic operations, including ‘domestic security operations’. Domestic security and response operations would likely comprise actions greater in scale and authority than domestic security operations as defined in the publication. Therefore one may surmise that security and response operations will be interagency, with many stakeholders and surrounded by legal and political sensitivities.

[6] Mark Smith, No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy: How Different Organisational Cultures Impede and Enhance Australia’s Whole-of Government Approach (Canberra: Australian Civil-Military Centre, 2016), p. 4; Dave Chalmers, ‘Interagency Leadership Lessons from the Northern Territory Emergency Response’, in Reflections of Interagency Leadership (Canberra: Australian Civil-Military Centre, 2021), pp. 10–11.

[7] ADF-I-3 Domestic Operations, pp. 13–14, 31–35 and 54–64.

[8] Ibid., p 26.

[9] Stahel, ‘Auftragstaktik’, p. x.

[10] Ibid., p. x.

[11] Ibid., p. x.

[12] Ibid., p. x. The author appreciates that the Wehrmacht did not consider the ‘operational level of war’ as a distinct doctrinal concept; the term is used here to enable the contemporary reader to understand the context of Auftragstaktik’s application (or lack thereof) during the Second World War. For a recent Australian perspective on the debate over the existence of the operational level of war, see Jeremy Barraclough, ‘Does the Operational Level of War Exist?’, CoveTalk presentation, 29 March 2023, The Cove, at: https://cove.army.gov.au/article/covetalk-2-div-pme-series-operational-level-of-war.

[13] ‘Instrumental and Value-Rational Action’, Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instrumental_and_value-rational_action (accessed 28 February 2025); Andrew McWilliams-Doty, ‘Instrumental Rationality vs. Value Rationality. Would You Rather Be “Right” or Effective?’, Medium, 25 October 2022, at: https://medium.com/@amdoty90/instrumental-rationality-vs-value-rationality-604884455337.

[14] ADF-P-0 Command, p. 23. Although not explicitly discussing mission command, Chapter 10 of ADF-I-5 Decision Making and Planning Processes (2024) also places great emphasis on the importance of raising the professional mastery of commanders and staffs.

[15] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), p. 58.

[16] Australian Government, National Defence Strategy 2024 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), pp. 27–29.

[17] Joint Concepts, ADF Capstone Concept APEX (2024); Joint Warfare Development Branch, ADF Theatre Concept ASPIRE (2023).

[18] Joint Warfare Development Branch, Concept Lantana, pp. 19–20.

[19] Australian Army, The Australian Army Contribution to the National Defence Strategy 2024 (Department of Defence, 2024), p. 16.

[20] Australian Army, Land Contributions to Homeland Defence Concept of Employment (Department of Defence, 2025), p. 11.

[21] This does not mean that the states and territories necessarily have the lead in all circumstances; rather, a state or territory retains the responsibility for operational management of its police forces within the state/territory. For example, the New South Wales Counter Terrorism Plan states that if a ‘national terrorist situation’ exists, the overall responsibility for policy and broad strategy transfers to the Australian Government (via the National Crisis Committee) but New South Wales retains control of operational management and deployment of its emergency services within the state. NSW Government, New South Wales Counter Terrorism Plan (2018), pp. 18–22.

[22] ADF-I-3 Domestic Operations, p. 44.

[23] See Samuel White, Keeping the Peace of the Realm (LexisNexis, 2021); David Thomae, ‘Keeping the Peace of the Realm’, Adelaide Law Review 43, no. 2 (2022), pp. 1018–1022.

[24] ADF-I-3 Prisoners of War, Internees and Detainees (2024), pp. 1–4.

[25] Australian Army, Land Contributions to Homeland Defence Concept of Employment, pp. 21–26.

[26] ADF-P-0 Command, pp. 22–23.

[27] At the time of writing, the concept of how and by whom PWID operations would be undertaken in a domestic setting was unclear; it, like the wider concept of security and response operations, remains a ‘work in progress’.

[28] The author differentiates between public affairs actions as information actions directed towards the Australian population, and information operations which are directed towards the adversary.

[29] ADF-P-0 Command, p. 30.

[30] David Connery and Tim Dawe, ‘Army-Police Interoperability: Collective Contributions to Future Land Power’, Land Power Forum, 12 June 2015.

[31] ADF-P-0 Leadership, p. 34.

[32] Ibid., p. 35.

[33] Ibid., p. 40.